[Estimated time: 14 mins]

When people speculate about the effects of AI on “economic growth”, they often assume economic growth will increase human welfare. Now, economists know that GDP per capita is not a measure of welfare. But, historically, GDP per capita has been pretty reasonably correlated with other measures of welfare. So you might hear them say, “yeah, yeah, there are good things like quality of relationships that GDP doesn’t measure, and some bad things like wars might boost GDP, but overall it’s still a pretty good welfare indicator”. The acknowledgement that economic growth and welfare are not the same thing often comes in the form of a brief disclaimer — a minor corrective that shouldn’t distract us from GDP’s overall signal.

My objections with GDP run a bit deeper than that. In this post, I argue that:

- GDP per capita has never been a measure of well-being.

- Up to now, I accept that GDP per capita has been a pretty decent proxy for well-being.

- However, the use of GDP per capita as a welfare proxy has already under pressure:

- when comparing wellbeing across rich countries; and

- when measuring the wellbeing impact of digital products (e.g. email, search engines, and Google maps).

I expect the relationship between GDP and well-being will come under further pressure as we enter the age of AI.

GDP has never measured well-being

It’s not just that GDP per capita is an “imperfect” measure of wellbeing. It’s that it’s never been a measure of well-being at all.

Okay, I hear you say, but GDP measures output. And, so long as we produce mostly good things, can’t we treat increases in GDP as increases in well-being?

That is sort of true, but GDP doesn’t even measure output accurately. For convenience, economists talk about GDP and output as if they were one and the same. However, there are two important reasons why GDP inaccurately measures output.

GDP only measures traded output

The first is that GDP only measures output that is traded.1One exception is that GDP usually does include the imputed rent value of owner-occupied housing. If I grow and eat my own vegetables, their value will never show up in GDP. If I buy them from the supermarket, they will. Similarly, if I look after my own kid and you look after yours, that won’t show up in GDP. But if we pay each other $100 to look after each other’s kids, that adds $200 to GDP, even though the same amount of childcare is “produced” in both cases.

By itself, this isn’t a big deal, because there are limits to how much we can individually produce. Manufacturing benefits from economies of scale, and trade is needed to produce anything at scale. So even though GDP does not measure all output, it should still correlate very strongly with output.

GDP measures amount of trade, not gains from trade

However, the second issue with GDP is that it only measures the amount of trade in an economy, not gains from trade. This point is crucial, especially when we discuss AI later.

Trade is only good because it is a “win-win” for both sides. Two parties won’t voluntarily enter into a trade unless they both expect to gain from it. Economists use the term “surpluses” to describe these gains from trade—the consumer surplus measures how much a consumer gains from trade, while the producer surplus measures how much a producer gains.2This should not be confused with the term “trade surpluses”, which describes the situation when a country exports more than it imports.

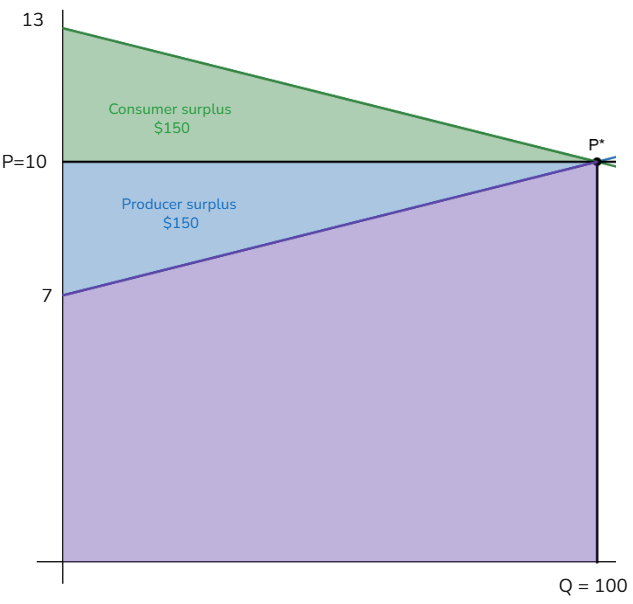

Here’s a standard econ 101 graph showing the difference between consumer and producer surpluses and GDP.

Don’t worry if you don’t like graphs—the key point is that what we ultimately care about (the gains from trade) are the blue and green triangles, which add up to $300. But what GDP actually measures, is the blue triangle combined with the big purple area, which has an area of $1000 (= $10 price x 100 units traded).

The problem is that even though gains from trade are ultimately why we care about trade, those gains are really hard to measure. GDP does not capture the green triangle, which represents the difference between what consumers were willing to pay for an item and how much they ended up paying for it. When consumers place a higher value on the item than they ended up paying, the trade makes them better off. For example, if I pay $10 for a book that I would’ve been willing to pay $13 for, I enjoy a $3 consumer surplus. In contrast, I might pay $10 for an app subscription that I think is only just worth $10. In that case, my consumer surplus is zero, even though the app subscription contributed just as much to GDP as the book did.

GDP cannot capture the green triangle because the government does not have the ability to look into people’s hearts and work out how much they truly value an item at. All it sees it the price the item traded at. So I’m not claiming some grand conspiracy by economists or politicians here—GDP is a perfectly sensible alternative given the real-world limitations we face. We just can’t lose sight of the fact that it measures the amount of trade, not the gains from trade.

Why GDP has been a decent proxy for well-being so far

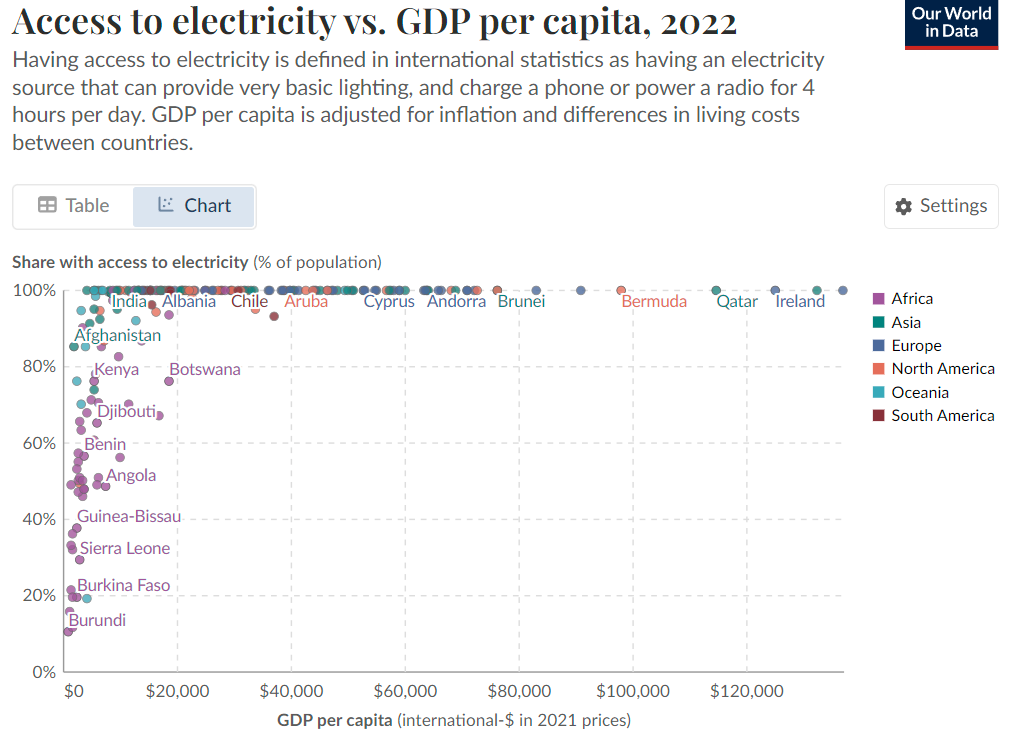

Despite my gripes with GDP, I can accept that it has been a reasonable proxy for well-being so far. GDP per capita is positively correlated with a variety of obviously good things (like interpersonal trust, access to electricity, literacy rates, life expectancy, and improved sanitation) and negatively correlated with some obviously bad things (like malnutrition, disease burden). I can think of at least two reasons for this.

First, there is clearly some relationship between GDP and gains from trade, because you can’t get gains from trade without trade. However, as I pointed out in my last post, it’s theoretically possible to increase gains from trade while reducing GDP. The example I gave was when a new technology helps us produce things more effectively and demand doesn’t rise. Conversely, as I will later explain, it’s also possible to shrink gains from trade while increasing GDP.

The second point is that some intangible things like functioning institutions, political stability, absence of corruption, and high levels of impersonal trust likely contribute both to well-being and to levels of trade. A country riven by political violence may struggle to deliver public goods like a working electricity grid or decent healthcare system, and political instability may make people reluctant to undertake the long-term investments that would boost trade.

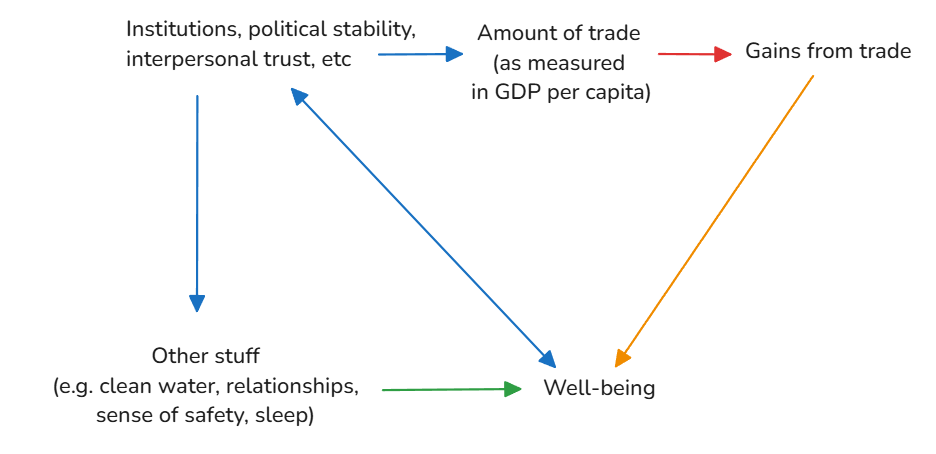

In other words, I see the causal diagram as being less like this:

And more like this:

(See my summary of The Book of Why for more on causal diagrams.)

This is still a highly simplified model, and I expect the real-life relationships are far more complex than the above. I also don’t expect any of the arrows above to represent linear relationships. My aim with this diagram is just to explain why GDP per capita can correlate strongly with well-being, even though it’s not a measure “of” well-being. In my view, the two key points are:

- The mechanism by which trade improves well-being is via gains from trade. So while I still believe there is a causal link between increased trade and well-being, it’s important to be aware of this mechanism because, as I’ll explain in my next post, it can be disrupted.

- Intangibles such as institutions, political stability, and interpersonal trust are likely to be confounders. They increase both GDP per capita and well-being, strengthening the positive correlation we see.

But GDP as a proxy for well-being has come under pressure

Comparing well-being across rich countries

As I explained above, we see GDP per capita is positively correlated with a bunch of good things and negatively correlated with some bad things. However, the good and bad things I referred to show strong threshold effects. Not having access to electricity certainly lowers my well-being. But past a certain threshold, you can’t raise my well-being by giving me more and more electricity.

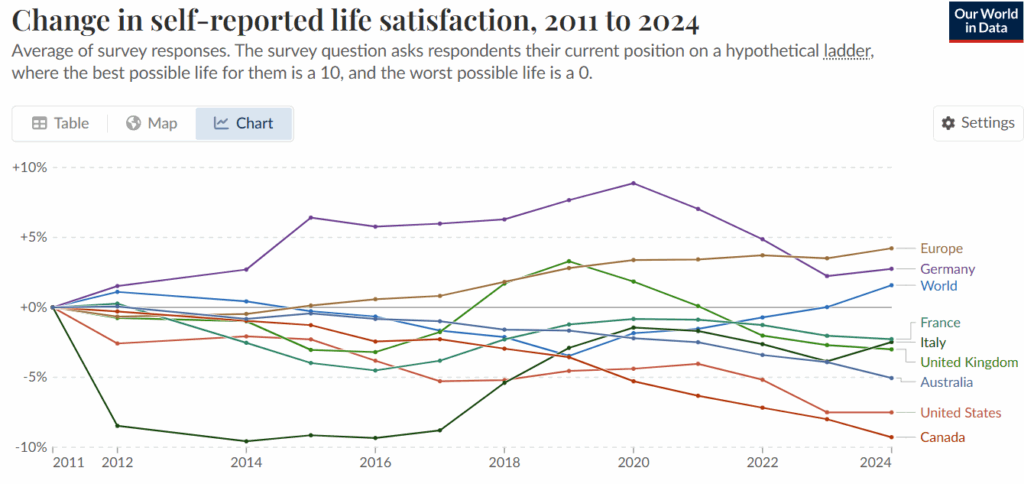

Indeed, if you only look at countries above, say, $40,000 GDP per capita, many of the correlations I referred to above disappear entirely: Access to electricity; Literacy; Life expectancy; Sanitation; Malnutrition; and Disease burden. There appear to be some correlation with Interpersonal trust, but a pretty weak one. Interestingly, I don’t see any correlation with GDP per capita when looking at Self-reported happiness, but I do see one with Self-reported Life Satisfaction. Self-reported happiness measures have tons of flaws though, so take that for whatever you think it’s worth.

The thing is, almost all countries with at least $40,000 GDP per capita have already maxed out on “obviously good” things and avoided most of the “obviously bad” things. And $40,000 is a fairly generous threshold — plenty of countries above $20,000 seem to have already hit the most important thresholds.

Some researchers have tried to come up with broader welfare measures, such as the UN’s Human Development Index and Jones and Klenow’s consumption-equivalent metric. These tend to show very strong correlations with GDP per capita. However, these welfare measures themselves include economic income measures,3The HDI uses gross national income (GNI) per capita, which is very similar to GDP, while Jones and Klenow use consumption, which is a component of GDP. so it’s perhaps unsurprising that the final measures are highly correlated with GDP.

Are Europe, Australia and Canada falling behind the US?

I want to briefly address some concerns I’ve heard about how Europe, Australia and Canada have fallen behind the US in GDP per capita growth. These concerns are often played up by opposition politicians, but plenty of well-meaning, apolitical people seem to genuinely worry about this too.

Personally, I am sceptical that pursuing US-style economic policies in an attempt to boost GDP growth would do much to improve the lives of (Western) Europeans, Australians and Canadians, who are already rich by world standards. The US’s strong economic growth hasn’t translated into decisive outperformance on things such as life satisfaction, interpersonal trust, suicide rates, leisure time, or even life expectancy. To the contrary, the US appears to be a laggard on many of these dimensions.

Now, I admit all of these measures have flaws and you can query how much weight to give each measure. Nor do I want to pick on the US, which I understand is a very large and diverse country. But what makes a life good is inescapably subjective.

To be clear, this doesn’t mean I think economic policies that will boost economic growth are automatically bad. There are plenty of sensible pro-growth, pro-welfare policies that Europe, Australia, and Canada (and the US) probably should be pursuing. Not everything involves a trade-off between growth and welfare, and each policy needs to be assessed on its own merits. All I’m saying is that GDP per capita does not appear to be a reliable yardstick for comparing between already-rich countries.

The Internet

GDP has also been terrible at measuring the welfare gains brought by the Internet. Many of the digital products we enjoy (including hopefully this blog!) are free. Or at least they’re much cheaper than users are willing to pay, meaning that GDP is particularly bad at measuring their gains.

In a 2018 working paper, economists Brynjolfsson, Collis and Eggers tried to estimate consumer surpluses for a variety of digital services by asking people how much they’d be willing to accept in order to stop accessing a service for a period. To incentivise people to give realistic answers, they enforced some of those choices. The study found massive consumer surpluses from search engines ($17,530 per person per year), email ($8,414) and digital maps ($3,648).4There are some questions over how representative the researchers’ sample was, and also differences between what consumers are willing to pay for a service vs what they are willing to give up to stop using one. But this just illustrates how hard it is to measure consumer surpluses, so don’t get too hung up on the precise figures.

Of course, your email provider cannot charge anything close to $8,414 per year because they do not have a monopoly on email. If they tried, virtually all their customers would promptly switch to another provider. Market competition among producers is what keeps prices low and allows consumers to enjoy gains from trade.

Using GDP as a welfare measure is especially problematic when prices are zero. This is the case in the emerging digital economy because most digital goods have nearly zero marginal cost and often a zero price. This makes it difficult to discern their contributions to welfare by looking at GDP calculations …

In the traditional economic model of perfect competition, firms are price takers, which means they don’t have enough market power to set the market price. The market price of a product should then ends up being its marginal cost—i.e. how much it costs to produce an extra unit of that product. With perfect competition, firms produce and compete until they drive prices down to match their marginal cost.

This traditional economic model falls apart when it comes to digital products, because marginal cost is virtually zero. The fixed costs involved in setting up the infrastructure for email or search services may be high. But once they’re set up, it costs almost nothing to provide services to just one more person.5Where network effects exist, such as in social media, the marginal cost might even be lower than the marginal benefit. This is why startups spend so heavily on acquiring new users, and why it’s so hard for new network-based platforms to displace existing ones. Network effects therefore naturally give rise to monopolies.

This is not an entirely new phenomenon. We see a similar dynamic with public goods, where fixed costs are high but marginal costs are low. If a government doesn’t charge their population for things like clean air, water, roads, public transit, libraries and well-functioning institutions, their true value will not show up in GDP. The cost that the government pays for those things do show up in GDP as government spending, but the value of those goods to the populace does not. For example, infrastructure required to provide clean drinking water gets counted at cost but the value of clean water to people does not.

Conclusion

GDP per capita does not measure well-being. However, we are currently in a paradigm where we do see reasonably strong correlations between GDP per capita and various measures of welfare. So, despite its flaws, GDP per capita it’s still a decent enough proxy for well-being in many cases.

But the relationship between GDP per capita and well-being is already under strain. Among wealthy nations above $40,000 GDP per capita, it’s hard to find correlations with “objective” welfare measures because so much of the “obviously good” fruit has already been plucked. Pressure on GDP per capita’s usefulness as a proxy for well-being is further exacerbated by the Internet, which has given us many free digital products and delivered large consumer surpluses.

We should not brush aside these challenges to the relationship between GDP and welfare as being mere edge cases. AI has the potential to transform our economy, perhaps more than the Internet did. Depending on how the technology goes, it has the potential to deliver many more digital products at a very low marginal cost. I think there’s a good chance we’ll see the relationship between GDP and welfare decouple further.

Let me know your thoughts in the comments below, especially if you think I’ve gotten anything wrong! I plan to address AI more explicitly in my next post (but you can probably see where I’m going with this anyway).

If you liked this post, you may also enjoy:

- Shouldn’t productivity gains reduce GDP?

- Book Summary: Why are the Prices So D*mn High? by Eric Helland and Alex Tabarrok

- Can zero-sum games negate productivity gains?

- 1One exception is that GDP usually does include the imputed rent value of owner-occupied housing.

- 2This should not be confused with the term “trade surpluses”, which describes the situation when a country exports more than it imports.

- 3The HDI uses gross national income (GNI) per capita, which is very similar to GDP, while Jones and Klenow use consumption, which is a component of GDP.

- 4There are some questions over how representative the researchers’ sample was, and also differences between what consumers are willing to pay for a service vs what they are willing to give up to stop using one. But this just illustrates how hard it is to measure consumer surpluses, so don’t get too hung up on the precise figures.

- 5Where network effects exist, such as in social media, the marginal cost might even be lower than the marginal benefit. This is why startups spend so heavily on acquiring new users, and why it’s so hard for new network-based platforms to displace existing ones. Network effects therefore naturally give rise to monopolies.

6 thoughts on “GDP has never been a measure of well-being”

Yeah I agree with all this. And I think your point about quality of life in USA vs other western countries is a good one.

However, as a thought experiment, if we had open borders and anyone could move anywhere, provided they agree to exclude themselves from social services, I think most people who would move would move to the USA over (say) Sweden or France or Canada.

Do you agree?

Is that thought experiment a better measure of quality of life than GDP per capita?

I agree that most people would choose the US, but I think it’s mostly because the US’s soft power and “marketing” (e.g. via Hollywood) has been so effective. The US also has a clear “unique selling point” by being, well, the US, whereas countries like CANZUK, the Nordics, and Western Europe may well split votes because their offerings are too similar. Also have to account for language – people might choose US over a country like Sweden simply because they don’t think they could integrate without learning Swedish, but that doesn’t reflect quality of life for natives. You also get a selection problem because the kind of people who migrate are far more likely to prioritise economic opportunity (especially if they are excluded from social services), whereas the kind of people who don’t migrate may prioritise other things – and the latter group will be much larger in numbers.

A better thought experiment might involve seeing which countries people would choose to settle in after being forced to live in a randomised sample countries for a few years each. (English countries will still get a language edge though.)

Do you think it’s likely that AI will cause a much larger decoupling between GDP and wellbeing, with goods and services becoming much cheaper and LMIC’s being able to improve without having to grow GDP as much?

Yes I do think we’ll see a larger decoupling between GDP and wellbeing, at least in developed countries (I’m less sure about the second half of your question re: LMICs). I think AI can go in a number of different ways – some of those ways could improve welfare considerably and boost GDP at the same time; some could improve welfare without boosting GDP; and some could boost GDP without improving welfare. It will really depend on what AI is able to do and how competitive the market will be, and where the bottlenecks lie. I’m still working through my thoughts on this and plan to follow up with a post once I’ve sorted them out.

The other point, which I probably should’ve mentioned in this post, is that GDP per capita tells you nothing about how income/wealth is distributed within a country. If AI increases inequality (which I expect it to), that also points to GDP becoming less relevant as a proxy for welfare.

Are you suggesting that AI is unique in the decoupled effect it’ll have on GDP/well-being, or just that most developed countries are at the stage where ANY large boost to GDP would be largely decoupled from well-being?

More the latter. I think it’s possible AI will play out similarly to other digital products (high fixed costs, low marginal costs) where GDP won’t capture the consumer surpluses that AI generates. But I also think it’s possible it will play out in the opposite way, where GDP increases a lot even as consumer surpluses shrink (e.g. because AI could allow companies to price discriminate more effectively). It really depends on how the technology develops and there are still lots of unknowns at this stage.