In How Asia Works, Joe Studwell sets out the three-part formula that bucked the Washington Consensus and propelled East Asian economies like Japan, Korea, Taiwan and China to developmental success.

[Estimated reading time: 30 mins]

Buy How Asia Works at Amazon (affiliate link)

Table of Contents

Key Takeaways from How Asia Works

- East Asian economies such as Japan, Korea, Taiwan and China became developmental success stories by following a 3-part formula:

- First, improve agriculture through land reform.

- Second, build up manufacturing using industrial policy with export discipline.

- Third, direct the financial system towards these two aims.

- Agriculture is important because it employs the vast majority of people in poor countries:

- Land reform ensures people have incentives to be productive and not just seek rent.

- Smallholder farming (gardening) is surprisingly productive. It takes a lot of labour, but labour is cheap for developing countries.

- Boosting agricultural yields reduces reliance on food imports and generates surpluses, which create a domestic customer base for industry.

- Manufacturing is key because it makes the most effective use of large but relatively low-skilled workforces and helps countries move up the value chain.

- Industrial policy can be very costly and “inefficient” in the short-run but the goal is to produce long-term technological learning. The investments may take decades to pay off.

- Export discipline is crucial, as it provides objective, market-based information about which firms are worth supporting. Don’t just “pick winners” at the outset, and bewilling to cull losers.

- Financial system:

- Developing states tend to lack the state capacity required for a full tax system, but can use the financial system to achieve their policy goals.

- Banks are easier to control than bond- or stockmarkets. Cheap loans is a form of grant or subsidy, while limiting deposit interest rates is a form of stealth taxation.

- If left alone, money will tend to flow towards real estate and stockmarket speculation and consumer spending rather than long-term technological learning.

- Unlike the East Asian countries, the Southeast Asia mostly followed the “free market” Washington Consensus:

- Malaysia was the best of the southeast Asian countries in that it attempted industrial policy, albeit somewhat clumsily.

- Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines all liberalised too early. Although they saw some strong growth initially, it didn’t last, and they still haven’t fully recovered from the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

- Industrial policy should not last forever. At some point, countries probably should liberalise trade and markets. When and how is unclear, and economists should focus more on this.

Detailed Summary of How Asia Works

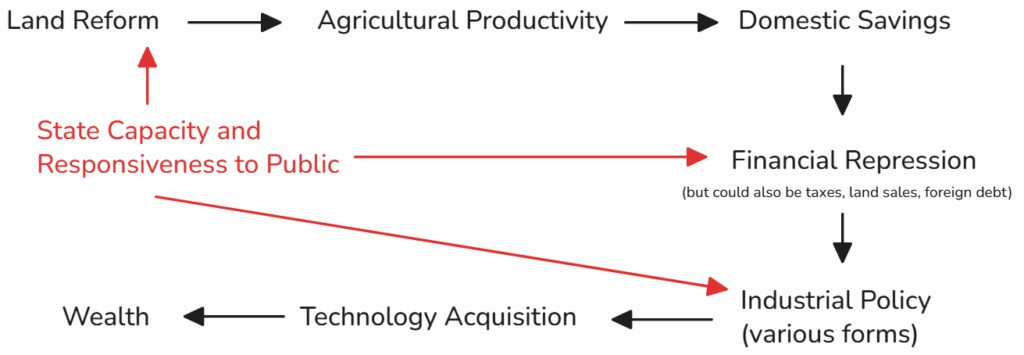

I’ve used some causal diagrams to try and set out Studwell’s theory visually. Here’s what I ended up with —click here for an explanation. (Note that the red parts are my own additions, as Studwell doesn’t really talk about state capacity.)

East Asian vs Southeast Asian development

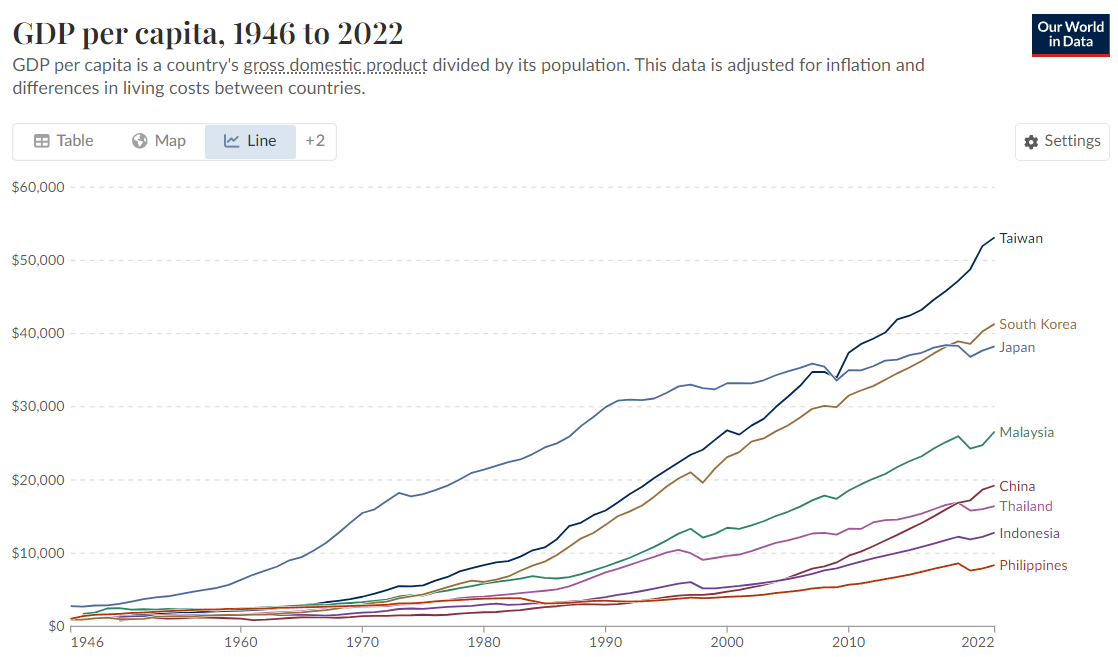

At the end of WWII, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, China, Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand were all similarly poor. All 7 of these economies grew rapidly after WWII, with growth rates of at least 7% per year for over a quarter century.

But while the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997 didn’t hurt the East Asian group too much, (Japan, Korea, Taiwan and China) the Southeast Asian group (Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand) was severely impacted. The difference between the two groups came down to the different interventions made by their governments in the preceding decades.

The Southeast Asian countries were “technology-less” developing nations. Their exports are not in the high-value-added parts of the supply chain, but in the more commoditised, low-value parts of foreign multinationals’ supply chains. So when foreign investment dried up in the financial crisis, they slid backwards.

Source: Our World in Data

The Washington Consensus

Studwell blames the Southeast Asian countries’ lack of success on their adherence to the Washington Consensus, developed in the 1980s. The World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the US Treasury all thought that free market policies were appropriate to all economies, no matter what stage of development they were at.

However, rich countries used tariffs and protectionism a lot when they were developing. In fact, no reasonable-sized country managed to become rich without industrial policy.

Example: Thailand’s as a “star pupil”

Thailand’s central bank has been the most independent and orthodox central bank in southeast Asia. The Bank of Thailand has maintained close relations with both the World Bank and IMF, who have consistently pushed for financial deregulation and provide the Bank’s staff with ongoing training. From 1991, Thailand’s interest rates were almost completely liberalised, meaning it had no loan or deposit interest ceilings.

This deregulation led to a boom based on lending for consumer spending and stock and real estate speculation. In the decade leading up to the 1997 financial crisis, Thailand was the world’s fastest growing economy. The Bangkok stockmarket index more than doubled between 1990 and 1996.

But Thailand was where the Asian Financial Crisis began, and the country was hit hard. The government had pegged the Thai baht to the USD, yet didn’t maintain capital controls, so the baht was freely tradable. So when currency traders began to short the baht, the country quickly ran out of foreign reserves to maintain the peg and was forced to let the baht float.

— Joe Studwell in How Asia WorksThe Thai government… remained the star pupil of the IMF and World Bank. That Thailand has fallen farther than any other country in the region since the crisis is an unfortunate comment on this status.

What about Hong Kong and Singapore?

Hong Kong vs Singapore are often held up, including by the World Bank, as examples of free market successes. But they are small financial and shipping hubs. Offshore centres are technically “parasitic” in that they can only exist if they have proper country “hosts” to feed on.

Normal states have larger, more dispersed populations, and their agricultural sectors act as a drag on productivity. Most countries can’t get rich with farming remaining a large part of their economies, unless they have a very high natural resource-to-population ratio, like in New Zealand or Denmark. Studwell therefore largely ignores Hong Kong and Singapore in his book. Their strategy simply cannot work for larger countries like China.

Why did East Asia ignore the Washington Consensus?

While Southeast Asia largely took advice largely from the World Bank and IMF, the East Asian countries succeeded by ignoring those agencies’ advice (or pretending to comply just enough to get them off their backs). Instead, their policy was influenced by Germany—particularly Friedrich List, one of most influential thinkers in the German Historical School.

List had formed his ideas during his time in the US, studying Alexander Hamilton’s “infant industry” arguments. He didn’t think the free-market theories by Adam Smith and David Ricardo applied to Germany’s current stage of development. While he agreed that free trade should be the ultimate goal, he thought that should only be after countries had already built up their manufacturing capacities through protectionism.

List’s ideas spread from Japan to the Japanese colonies of Korea and Taiwan, and later to China. (Interestingly, the US occasionally tolerated, and even paid for, the industrialisation of the friendly states of Korea and Taiwan after WWII — it just depended on which faction happened to be in control.)

1. Agriculture

Why is agriculture important?

Agriculture is important because, in the early stages of development, the great majority of people work in agriculture. Boosting agricultural yields reduces reliance on food imports and generate surpluses. These surpluses then create a domestic customer base for industry to start developing. A bunch of successful east Asian corporations from Japan, Korea and China started out making products for their rural markets.

Studwell calls land policy the “acid test” of a poor country’s government. Land policy is an entirely domestic affair and ostensibly within the government’s control. So land policy can tell us how much the leaders know and care about the bulk of their populations. Some of the key figures in the industrialisation of South Korea and Taiwan were sons of farmers, and the pioneering entrepreneurs in China overwhelmingly came from farming backgrounds. This type of social mobility is almost unheard of in south-east Asia.

Why land reform?

With free markets, yields tend to stagnate as populations rise because the demand for land increases faster than supply. If landlords can make more money collecting economic rents and consolidating landholdings than investing in irrigation, they’ll just collect rents. Many poor countries around the world have faced this same problem.

In east Asia after WWII, the difference was that the governments undertook radical land redistribution programs. These programs all had basically the same objective—to divide up the agricultural land equally among farming populations so that each household then owned a small farm. This led to various benefits:

- Good incentives. As owners rather than tenants, farmers were incentivised to invest their resources in maximising yields. In the East Asian states, yields increased drastically after land reform. Indeed, cross-country research has found a strong negative correlation between initial inequality in land distribution and long-term growth.

- Reliable jobs. Household farms can play an important welfare role since poor countries don’t tend to have unemployment benefits. During economic downturns, migrant factory workers can go home to work on their family farms instead of squatting in cities.

- Increased competition. While the US government was sceptical of land reform as being “socialism”, it was really the opposite. Giving households equal amounts of land to farm created conditions of near-perfect market competition.

Doesn’t efficient farming require scale?

Gardening can produce surprisingly high yields per square metre if you’re willing to put in the work. There is tons of evidence across many countries that as farm sizes increase, farm yields per hectare decrease. That’s because yields in small farms can be increased by all sorts of micro-optimisations like close planting, using trellises, and so on, which don’t work at large-scales. This is something that communist countries like Russia and China, as well as free marketers, all failed to appreciate.

The economies of scale that exist in agriculture are not in cultivation but in processing and marketing. In the first 10-15 years after the East Asian states shifted to small-scale farming, gross agricultural output increased by ~50% to 75%.

Small garden vs Big farm yields

In 2009, a well-known blogger, Roger Doiron, weighed all the fruit and vegetables that his 160 sq m kitchen garden produced and checked it against retail prices. He found the garden’s retail value was about $16.50 per sq m, equivalent to well over $100k per hectare.

For comparison, the wholesale price of corn (the US’s most successful large-scale farm crop) in 2010 was only $2,500 per hectare.

Rubber yields in Malaysia

Rubber plantations yielded 400 pounds per acre per year, while smallholder rubber yields ranged from between 600 and 1,200 pounds. This was because smallholders planted their trees more densely and tapped them daily, using labour to maximise their output.

As a country develops and the cost of labour increases, larger and more mechanised farms makes sense. Developing and developed countries should optimise for different things based on their resource constraints. In a developed country like the US, land is abundant while labour is scarce, so it should optimise for yield per hour worked. But in developing countries where labour is abundant and land is scarce, they should optimise for yield per hectare. Even if the yield per man hour worked looks terrible on paper, it’s still better than what those workers would otherwise be doing.

Policy is more important than geography

Sometimes people think that south-east Asia is relatively backward because it is “too hot”, while north-east Asia enjoys a temperate climate. But Studwell groups Taiwan with the East Asian success stories, even though it actually has a subtropical climate.

He also notes that Japan developed successfully with very little cultivable land—the lowest share of cultivable land of any country in East Asia (14%; Korea meanwhile is 20% while Taiwan is 25%).

History of land reform in Asia

Studwell goes into quite a lot of detail about the history of land reform in Asia. The East Asian countries all pulled off land reform pretty successfully. It was not always easy—it’s estimated that land reform contributed to hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of deaths in China. But it seemed to seemed to go more peacefully when the reforms were imposed from outside — e.g. US-supported land reform in Japan and Taiwan after WWII was much less bloody.

Southeast Asia never pulled off land reform successfully:

- The Philippines tried multiple times, each time doing the bare minimum to stave off civil war. One estimate put the amount of land distributed at merely 4% of cultivable land. The reforms were also implemented poorly with lots of loopholes. New landholders did not have the capital to invest in their farms and the state didn’t provide support, so many ended up leasing their land back to the former owners or taking on expensive debt.

- Indonesia followed the Philippines’ model with a similar lack of success.

- Thailand’s land reform was focused on public lands and led to almost no redistribution.

- Malaysia never even attempted it.

— Joe Studwell in How Asia WorksLand reform continues to be dismissed as too difficult, even though land inequality and agricultural dysfunction are at the heart of the world’s most dangerous societies.

2. Manufacturing

The next stage of development for emerging economies typically revolves around manufacturing. This is because:

- Manufacturing uses machines. Increasing productivity in services is slow because it depends more on people and training them up. With manufacturing, however, developing countries can just import machines and significantly boost the value of an average factory worker’s labour with only minimal training.

- Manufactured goods are traded much more freely than services. Most services require goods or people to travel in two directions. You can’t send your bike to India for repairs, for example. So genuine free trade in services would require the free movement of people worldwide.

What about India?

People often point to India as a country that developed through services, particularly in IT.

However, service entrepreneurs create far fewer jobs than manufacturing entrepreneurs. Twenty years after India launched its reform agenda in 1991, the IT sector employs merely 3 million people out of a 1.2 billion population — just 0.25%! By contrast, after 20 years of industrial policy in Korea, 30% of the labour force worked in industry.

People in rich countries often underappreciate how important manufacturing is in development because services are so much more dominant in rich countries. Yet the relatively small share of jobs in manufacturing is because of the vast productivity gains in manufacturing. For example, the UK manufactures 2.5 times what it did at the end of WWII in real terms, but with less than a third of the workers. [See also Shouldn’t productivity improvements reduce GDP.]

What is industrial policy?

Industrial policy refers to government policy that protects certain favoured industries in an attempt to boost a country’s long-term development. Almost every economically successfully country relied on protectionism in its formative stage. Countries in Europe and North America relied heavily on a variety of tariff and non-tariff import restrictions when they were industrialising.

On a short-term view, protectionism is expensive and inefficient because you are propping up firms that cannot compete internationally. But it can pay off in the long run if it gives the country a permanent, strategic advantage. And industrial policy can take a long time to pay off—Hyundai, for example, didn’t produce its first in-house car engine until 24 years (!) after the government began prioritising the automotive sector.

Industrial policy is like investing in your child’s education

Ha-Joon Chang has compared industrial policy to a parent investing in their child’s education. Sure, in the 19th century you could send your 10-year-old off to work in a factory and earn profits immediately. But most parents avoided doing this if they could, preferring to keep their children in school so that they could earn more in the long run.

A similar logic applies to developing countries. Free trade may look efficient because trading in a country’s current comparative advantage is most profitable in the short run. But for a developing country, that usually means staying in agriculture or doing low-value processing for foreign multinationals. To move up the value chain to higher-value goods (e.g. cars, shipbuilding, semiconductors), the state must intervene with a longer-term perspective.

— Joe Studwell in How Asia WorksDeveloping states … need to invest in learning before they worry too much about efficiency. They must walk before they can run.

There are many types of industrial policy

Industrial policy can take many forms, including:

- Tariffs. For example, Korea imposed tariffs on steel imports when it was trying to build up its domestic steel manufacturing base.

- Subsidies, tax breaks. The state might subsidise raw materials or give tax breaks to favoured industries. Some they even gave free or cheap land to favoured manufacturers.

- Building infrastructure. Roads, railways, ports, all help manufacturers reach bigger markets.

- State companies. These have played a significant role in China, Taiwan and Malaysia, and may be good options when a state hasn’t built up its regulatory capacity.

- Rationing bank credit. Discussed further below under “Financial system”.

- Support with technology acquisition. Governments in Japan, Korea, Taiwan and China all got involved in buying technology from foreign firms, often forcing them to hand over know-how in return for local market access.

- Physical coercion. Early on, Korea locked up most of its business elite in jail and forced them to sign agreements promising to donate their property if and when the government required it for national construction.

Example: Power turbine technology

In the 1980s, the Chinese government negotiated a deal with US company Westinghouse giving them market access in exchange for their thermal turbine technology. It then diffused the technology among half a dozen state sector engineering firms, which began to produce turbines in the 1990s.

Later, the government again helped those firms acquire hydropower turbine technology from multinationals like Siemens. State banks also offered cheap loans to encourage power equipment makers to export, starting with other developing states.

By the 2000s, China had built up the largest power equipment production capacity in the world. In 2009, China exported USD9 billion of power equipment and began expanding into eastern Europe.

Studwell argues that the state gets the most leverage when it uses the power it has (over banks, business licences, state-controlled assets, land etc) to channel private entrepreneurs towards its developmental objectives. This is usually more effective than taking over all aspects of entrepreneurship.

— Joe Studwell in How Asia WorksRents are the bait with which the successful developing state catches and controls its entrepreneurs.

Industrial policy can be carried out poorly, and indeed it has been various times, such in much of Latin America. But that doesn’t mean all industrial policy is bad. With any kind of learning, there will be some hits and some misses. Just like you don’t write off the whole idea of education when a child fails a test, you shouldn’t write off all industrial policy because of a few individual failures.

Export discipline

A common problem that arises with industrial policy is that entrepreneurs might direct their efforts towards obtaining protection and subsidies from the state (e.g. lobbying and corruption, rent seeking) instead of actually doing what the protection and subsidies are intended to achieve (i.e. technological learning with positive developmental spillovers).

Development is … a thoroughly political undertaking. If governments allow entrepreneurs access to what economists call ‘rents’ – sources of income at government discretion – without contributing to developmental objectives, this is a political dereliction of duty.

— Joe Studwell in How Asia Works

This is where export discipline comes in. Export performance provides an objective, market-based measure of how well a firm is doing. It’s relatively easy for a firm to make money in a protected environment at home—firms have an inherent advantage in their home markets because they naturally understand their local customers, the logistics are easier, and all the better if they get state subsidies on top of that. Competing globally is much harder.

So one way to limit rent-seeking is to link the protection and subsidies to firms’ export performance. This means continually testing and benchmarking firms that are given subsidies and market protection, and withdrawing that support if they don’t meet certain export targets. In Japan, firms’ depreciation tax deductions were determined by their level of exports. Meanwhile, in Korea, firms had to report their exports on a monthly basis in order to get access to bank credit.

Export discipline has been the key factor distinguishing successful industrial policy from failed industrial policy.

Not picking winners; more like culling losers

Critics of industrial policy often claim it requires the government to successfully “pick winners”, and that is very difficult to do well. But the successful East Asian governments didn’t just pick out a few firms and shower them with subsidies. (That was more Malaysia’s approach.) Instead, they linked protection and subsidies to certain goals or targets, while remaining agnostic about which firms would meet those targets.

The East Asian governments didn’t “pick winners” so much as “cull losers”, withdrawing support and licenses for firms that didn’t measure up.

Example: Korea’s car industry

During the 1970s and 1980s in Korea, direct and indirect state subsidies helped set up half a dozen auto makers. Over the next 30 years, most of those firms were killed off.

Today, only one survives — Hyundai, one of the most successful car firms in the world.

3. Financial system

After WWII, all the 9 major east Asian economies had domestic savings rates between 30 to 50%. These were high enough for any of them to industrialise and join the rich world. Unfortunately, some countries financed the wrong policies.

Successful states pointed their financial systems at their agricultural and industrialisation targets, with an eye to export discipline. To ensure that funds don’t flow to alternative investments offshore, they usually imposed capital controls.

Unsuccessful states, by contrast, let the market determine where funds would flow—usually consumer spending and real estate.

— Joe Studwell in How Asia WorksDeregulation policies do not empower a ‘natural’ tendency for finance to lead a society from poverty to wealth, they simply put short-term profit and the interests of consumers ahead of developmental learning and agricultural and industrial upgrading. There is no case for doing this when a country is poor.

Banks vs markets

It is easier for a government to point their country’s banks towards projects that support its agricultural and industrial development objectives, because governments usually have a lot of control over banks. To secure credit, firms had to show they met certain export quotas.

Bond and stock markets, by contrast, are much harder for policymakers to control. This is why entrepreneurs in developing countries lobby hard for deregulation of bond and stock markets. It’s harder for policymakers to see how funds from bond and stock issues are used. Financial regulation is one of the hardest areas of governance, even in developed countries.

Deregulated finance goes to short-term investments

Free market proponents usually argue that finance should be deregulated so that it seeks out the most profitable investments (perhaps with the acceptance that some externalities may need to be regulated separately).

But the returns from industrial policy investments take a long time to eventuate—sometimes even decades—so require patient capital. When firms seeking long-term technological investments make share issues, there’s often an initial euphoria followed by a quick sell-off once investors realise firms cannot deliver quickly the profits they expected would come.

Real estate speculation and consumer spending offer much quicker returns, so is where capital tends to flow in free capital markets. That’s what happened in southeast Asia and in Latin America after banks were privatised in the 1970s.

Financial repression can fund industrial policy

So where do banks get all the funds to lend to industrial policy, if the investments may take decades to pay off? For the East Asian economies, this has mostly been through their citizens’ domestic savings. (Korea had lower savings rates, so relied a bit more on foreign debt. This worked out for Korea, but is riskier.)

As mentioned above, in free capital markets, money tends to flow to areas where investors can get the highest returns, at least in the short term. This may mean real estate, share speculation, or foreign capital markets. So to keep savings “in” the country, the East Asian economies restricted capital outflows: Japan did so until 1980, while Korea and Taiwan until the 1990s. In Korea, it was illegal to even take an overseas holiday up until the 1980s!

On top of capital controls, the governments applied interest rate ceilings at rates well below market. Real interest rates were sometimes even negative as they failed to keep up with high levels of inflation. But savings didn’t collapse like many economists had expected. Savers simply weren’t that sensitive to deposit interest rates—they still saved because they needed to set aside money for future expenses (especially because there usually wasn’t much of a welfare safety net). Some private savings did find their way onto illegal “kerb” markets with much higher interest rates, but capital controls don’t need to be airtight to be effective.

Capital controls and interest rate ceilings are often referred to as “financial repression”. The cost is borne by retail savers and borrowers, and is essentially a hidden form of taxation. People usually put up with this when they could see their country industrialising and moving up the development ladder but, at some point, they may decide that the costs are not worth it. Studwell does seem to accept that, at some point, countries should deregulate their financial systems—it’s just hard to work out when that point is. But he has no doubt that Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines were pushed to deregulate prematurely, leading to asset bubbles that collapsed in the Asian financial crisis.

Industrial policy shouldn’t last forever

— Joe Studwell in How Asia Works[K]nowing how to regulate and how to deregulate are two different things.

There are at least two different types of economics:

- Economics of development — this is like an education process, and requires nurture, protection and competition.

- Economics of efficiency — this applies at a later stage of development, and requires less state intervention, more deregulation, freer markets, and a closer focus on near-term profits.

The same policies that help a poor country develop can create problems after it’s become rich. For example, even after Japan’s wages rose, the country did little to move its agriculture from prioritising yields per square meter to high yields per worker and maintained its agricultural subsidies and tariffs. This caused its agricultural productivity to plummet, while consumers continued to pay the cost. Similarly, large manufacturers built up by the state in Korea and Taiwan began to abuse their oligopoly positions, squeezing the margins of smaller, less-favoured downstream businesses.

Leave the developmental drawbridge down

Taking away agricultural protection once a country has developed is also good from a developmental perspective. Allowing other countries’ agricultural imports helps developing countries export their agricultural surpluses when their labour is cheapest.

But the switch is not an easy one to make. Unlike Japan, China did remove its agricultural subsidies while keeping farm small. This led inequality to soar, as urban incomes rose to more than 3x rural ones. And when Japan removed its capital controls and liberalised its financial sector in the 1980s, it experienced a massive surge in consumer lending as well as large asset bubbles in housing and stocks.

Finding out when to switch from development economies to efficiency economics is a difficult and interesting question that economists should spend more time working on.

Other Interesting Points

- Studwell omits Vietnam in order to simplify the structure of his book. He also omits “failed states” North Korea, Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar and Papua New Guinea from his book because he wants to focus on developmental strategies that have achieved some modicum of success. Moreover, the failed states are all closed off — if a country refuses to trade and interact with the world, it is virtually impossible to get ahead in development.

- It is dangerous to judge economic progress by growth rates alone. Brazil grew by more than 7% per year for more than 25 years through the 1960s and 1970s. But the Latin American debt crisis in 1982 revealed that much of the growth had been fuelled by debt and did not translate into genuine increases in productivity.

- The correlation between education and GDP growth is much weaker than most people imagine. The causal relationship seems to go development -> education rather than the other way around.

- The strongest evidence for education helping developing is for primary schooling, but some states like South Korea and Taiwan achieved strong economic growth with low levels of education (55% of Taiwanese were illiterate at the end of WWII, and 45% were still illiterate in 1960; South Korean literacy was lower in 1950 than in Ethiopia today). In contrast, states like Cuba have high levels of education but low growth.

- Studwell thinks the reason for this weak correlation is because a lot of critical learning takes place in firms, “on the job”, rather than in the formal education sector. Formal education might be more important once a country reaches the technological frontier.

- Friedrich List claimed that the British prime minister, William Pitt, carried a copy of The Wealth of Nations around to use in arguments with the French, to convince them that France “by nature France was adapted for agriculture and the production of wine”.

My Review of How Asia Works

How Asia Works was published in 2014 and is a little outdated as a result. For example, Studwell’s comments about how Chinese firms can’t compete in international consumer markets no longer seems to apply given the rise of Huawei, TEMU, Shein, Xiaomi, and BYD in recent years. (Funnily enough, Studwell refers to BYD as a cautionary tale of a private firm that struggled to compete with public sector JVs and “peaked” in 2008 with a market cap of US$25 billion. Today it’s at ~US$130 billion.) But the book holds up pretty well overall, and I still found it a valuable read in 2025.

The book raised a lot of thought-provoking ideas, such as:

- Export discipline. The idea of using exports as an objective metric to decide which firms to reward makes a lot of sense. I’d never thought about the distinction between exports and domestic sales being a significant one, but obviously the two are very different in a protected market. Using exports in this way is also an example of a pull mechanism for promoting development, which leverages market information and therefore tends to be more cost-efficient than push mechanisms.

- Different parts of the supply chain capturing different amounts of value. Not all exports are the same. Some—like contract manufacturing for multinationals, or commodities production—are low value-added and highly competitive. To move up the value chain to an area with less global competition, states/firms need to build up their technological capacity, which serves as a barrier to entry. It was interesting to hear how Malaysia took Japanese firms’ advice at face value and got ripped off in the process (because the Japanese didn’t want to share their valuable technology), while Korea and China were less trusting of foreign multinationals.

- Controlling upstream businesses. Upstream businesses (including banks) seem more likely to earn location-specific rents—e.g. they may control utilities, infrastructure, minerals, or other natural resources, or may require greater economies of scale and therefore be naturally monopolistic or oligopolistic. Such businesses require greater “discipline”—whether through direct state ownership, extra taxes, or regulation—else they will squeeze downstream producers. This is a generalisation of course—there overlap between “upstream businesses” and “businesses earnings economic rent” is not a perfect one, but it seems like a good place to start.

- Financial repression. I’d never heard arguments in support of financial repression before (though I suppose proponents wouldn’t call it “repression”). It’s wild to think it was illegal for most people to take an overseas holiday in Korea even into the 1980s. Some of the points Studwell brought up against the “independent central bank” orthodoxy were interesting, and highlighted how blurry the line between monetary and fiscal policy can be.

But I did have a few quibbles with the book. I personally found it a rather challenging read, with a fair bit of repetition and some overly long sentences. Studwell adopts a narrative writing style, diving into the history for each country with considerable detail. This can make it tricky to pin down the claims he is making—often I couldn’t tell if he was making a narrow claim about what happened at a particular time and place, or a more general one about how the world works.

The parts about moving off industrial policy were also relatively weak. Though Studwell acknowledges it’s hard to know when to move off industrial policy, he seems confident that at some point this should be happen. Yet it’s not obvious that the arguments for state intervention disappear entirely at more advanced stages of development, and many today seem to think industrial policy is appropriate for the US even now (under both the Biden and Trump administrations). Perhaps Studwell just wanted to make more modest claim about how policies are context-dependent, and that what works for developed countries isn’t necessarily appropriate for developing countries. If so, that’s unobjectionable. But I was left with the impression that Studwell was mostly just trying to placate mainstream economists here, as he doesn’t put up many strong arguments against those who would support industrial policy for developed countries.

Overall, Studwell does a much better job than Ha-Joon Chang in setting out the case for industrial policy and the book is well worth a read. I definitely don’t think anyone should come away thinking “yay industrial policy for all”, but hopefully the book promotes more nuanced thinking about development and how context-dependent policies can be.

Let me know what you think of my summary of How Asia Works in the comments below!

Buy How Asia Works at: Amazon <– This is an affiliate link, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through it. Thanks for supporting the site! 🙂

If you enjoyed this summary of How Asia Works, you may also like:

2 thoughts on “Book Summary: How Asia Works by Joe Studwell”

When reading this summary, my mind can’t help but drift to counterfactuals.

For instance,

>However, rich countries used tariffs and protectionism a lot when they were developing. In fact, no reasonable-sized country managed to become rich without industrial policy.

or the story of Thailand’s economic collapse in the late 90s.

These occurrences mold our understanding of the country development playbook, and knowing that always makes me a bit skeptical when reading about what is effectively modeling a highly complex, variable system. Could things have played out differently? And if they did, would Joe be writing about how important it is to “nurture” a country with industrial policy and avoid laissez-faire economics until later on?

Yes, I think we should always approach theories like this with some skepticism – as you say, development involves highly complex and variable systems. But I don’t think Joe’s argument is merely “all the successful countries did industrial policy” – I think the causal chain he sketches out also makes sense. Referring back to my causal diagram – perhaps there are other causal paths to Technology Acquisition or Wealth that don’t require Industrial Policy, but that wouldn’t “disprove” the path Joe points out. (Also worth noting that the path Joe points out is not a failproof recipe – he himself is quick to acknowledge that there are many ways to screw up Industrial Policy.)

I would hope that if things played out differently and we saw multiple medium/large countries get rich purely through laissez-faire policies, Joe would have written parts of his book differently.