This summary of The Art of Gathering: How We Meet and Why It Matters by Priya Parker offers practical advice on how to host meaningful and transformative social gatherings. It’s worth a read even if you’ve never thought of yourself as much of a “gatherer”.

Estimated time: 23 mins

Buy The Art of Gathering at: Amazon (affiliate link)

- Key Takeaways from The Art of Gathering

- Detailed Summary of The Art of Gathering

- My Review of The Art of Gathering

Key Takeaways from The Art of Gathering

- Gatherings don’t have to suck. But many do, because their hosts focus too much on food, decoration and logistics and not enough on the people.

- Purpose is the foundation of a meaningful gathering:

- A strong purpose is specific, unique, and disputable.

- Your purpose should act as a decision filter for many other choices such as who to invite, where to hold your gathering, and what rules to set. A vague purpose like “to celebrate” or “to network” will not help you make such decisions.

- Focus on people and purpose:

- Don’t be afraid to exclude people. More is not always merrier.

- A group’s size will affect its dynamics—what is appropriate depends on your gathering’s purpose.

- People behave differently in different settings. Pay attention to your venue’s size and layout.

- Exercise your generous authority as host:

- As a host, you have a certain amount of authority. Use it.

- Use your authority to protect guests, equalise people, connect them, and perhaps provoke good controversy. Don’t be a “chill host”—your guests came to your gathering because they trusted you.

- Exercise your authority generously for the sake of your guests, rather than for your own benefit.

- Use explicit rules to create a temporary alternative world:

- Explicit rules can be liberating and allow attendees to act in ways they normally wouldn’t. This can help them be more present and engage more meaningfully.

- Controversy can be good and inject life into gatherings. But you will need structure and rules to keep the controversy constructive.

- Open and close with intention:

- Your gathering starts when people first hear about it, not when they arrive.

- Openings and endings are important—don’t waste them on logistics or lists of “thank-you”s.

- Close your gatherings thoughtfully, perhaps with a “last call”, instead of letting them simply peter out.

Detailed Summary of The Art of Gathering

Gatherings don’t have to suck

Gathering occurs when we bring people together for a reason. Gatherings shape the way we think and feel about the world. And yet, much of the time we spend in gatherings disappoints us.

Parker explains that this happens because hosts often fail to adopt an active role in bringing people together. They get advice from chefs or event planners, who focus more on the food, decorations and logistics, and just hope that the chemistry will somehow take care of itself. Sometimes this works, but it commonly fails. Instead, gatherers should focus on the people.

Parker is a professional facilitator with a background in group dialogue and conflict resolution. The Art of Gathering is based on Parker’s own experience as well as her interviews with over 100 other gatherers. Her advice is drawn from all types of gatherings, from intimate dinner parties to large conferences.

I believe that everyone has the ability to gather well. You don’t have to be an extrovert. …

The art of gathering, fortunately, doesn’t rest on your charisma or the quality of your jokes.

Not every suggestion in the book will make sense for all gatherings—you will have to decide what makes sense in the context of your gatherings. Some gatherings might break every rule in this book and still turn out great.

Purpose is the foundation of a meaningful gathering

When we gather, we often confuse the category of a gathering (birthday party, board meeting, networking event) with its purpose. This can lead to formulaic gatherings based on some outdated model of the world, rather than serving our current, particular needs.

Example: What is the purpose of a baby shower?

When Parker got pregnant, her husband asked if he could come to the baby shower. At first, she thought it didn’t make sense.

But then she realised that, traditionally, baby showers are women-only gatherings because they reflected a time when the only person who really needed to prepare for parenting was the mother (and some of the women around her). Following that traditional script didn’t really make sense in their more egalitarian relationship, where both Parker and her husband wanted to get ready for their new roles as parents.

A meaningful gathering needs a purpose that is specific, unique, and disputable. A specific and disputable purpose (meaning, one that not everyone would agree with) acts as a filter for making decisions about who should be there, where it should happen, and what rules to set, while a unique purpose helps distinguishes your gathering from all others of the same general type.

The purpose of your gathering is more than an inspiring concept. It is a tool, a filter that helps you determine all the details, grand and trivial. To gather is to make choice after choice: place, time, food, forks, agenda, topics, speakers.

Sometimes gatherers try to jam a bunch of mini-purposes into a single gathering. Other times, people are reluctant to commit to a specific purpose out of modesty. They want to appear “chill”, like they don’t care too much. But gathering well isn’t a chill activity and requires intentionality.

To find your gathering’s purpose, ask “why” repeatedly until you hit a deeper value or belief. Another approach is to reverse-engineer an outcome: think about what you want to be different because you gathered, and work backward from there. If this exercise reveals that there isn’t a strong reason to meet at all, you may be better off doing a casual hangout or just giving people their time back.

Focus on people and purpose

Who should you invite and exclude?

Your gathering’s purpose will be put to the test as soon as you have to decide on the guest list. Inviting people is easy, but excluding them can be hard. A disagreement over who to exclude may reveal a deeper disagreement about the gathering’s purpose in the first place.

However, thoughtful exclusion is vital. Some people will actively undermine and be harmful to your gathering’s purpose so you definitely want to keep them away. But others, like “Bob”, might be perfectly pleasant but still detract from your purpose by diluting its focus and taking attention away from who or what the gathering is really for. Adding people who aren’t that relevant can make it harder for others to form meaningful connections with each other. In smaller gatherings, every single person can change the group’s dynamics.

The crux of excluding thoughtfully and intentionally is mustering the courage to keep away your Bobs. It is to shift your perception so that you understand that people who aren’t fulfilling the purpose of your gathering are detracting from it, even if they do nothing to detract from it.

How many people?

In Parker’s experience, there are certain “magic” group size numbers that will shift the dynamics of a gathering. Hers are:

- 6 people — good for intimacy, sharing, and discussion through storytelling. Not good for diversity of viewpoint, and not much room for dead weight.

- 12 to 15 people — still small enough to build trust and intimacy and small enough for a single moderator, yet big enough for a diversity of views. Parker notes that many start-ups seem to have people problems once they get beyond this number.

- 30 people — this starts to feel like a party, and will be too big for a single conversation.

- 100 to 150 people — many organisers think this is the ideal size for a conference. There’s still some possibility of intimacy and trust and everyone can still meet everyone if they make the effort.

Where to host it?

Your gathering’s purpose should also guide where you host it and how you organise the space. Don’t choose a place solely based on cost or convenience—that is letting logistics override your purpose.

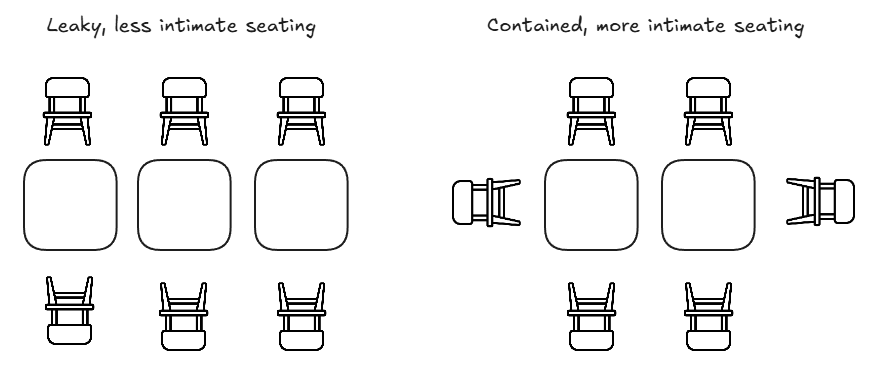

Different venues bring out different behaviours in people. Sometimes you may have to rearrange a room so that it better serves the gathering’s purpose. A contained space with a clear perimeter can help guests to relax and engage more fully in the group conversation. By contrast, a “leaky” space with ill-defined boundaries can inhibit intimacy. Defining a space could be as simple as putting down a blanket for a picnic instead of sitting on the grass, or moving furniture around to reduce gaps between people.

The size of your venue also matters. Large spaces can make it harder to mingle, and reduces the chance of an accidental encounter leading to a meaningful connection. You might need to cordon off part of a larger space with furniture or props to make it smaller. Of course, you don’t want the space to be too small, else people will feel boxed in and uncomfortable.

This explains why guests often gravitate toward kitchens at house parties later in the evening—people instinctively seek smaller spaces to maintain the right social density as the number of guests dwindle. Studies also show that switching rooms throughout an event can also help participants better remember the different parts of the experience.

Exercise your generous authority as host

You have authority as a host

Many hosts feel uncomfortable acknowledging the power they have over their gatherings. They just want to be a relaxed, “chill” host and let the event unfold naturally. But abdicating your power doesn’t make power dynamics go away. Instead, you leave a power vacuum for someone else to fill—often at the expense of the gathering’s purpose. The loudest voices, highest-status individuals, or most forceful personalities are more likely to take control.

Remember—your guests attended your gathering because they trusted you as the host. When you abdicate your authority as host, you are failing them.

Hosts assume that leaving guests alone means that the guests will be left alone, when in fact they will be left to one another.

Using your authority doesn’t have to be loud or dramatic. It could be as simple as rescuing a guest from a one-sided conversation or gently reminding people what the purpose of the meeting was.

When to use your authority

Important ways to use your authority as a host include:

- Protect your guests. This could mean protecting them from other, potentially domineering, guests or from boredom, tangents, or other distractions like phones.

- Equalise people. Most gatherings include people of different status levels, whether formal or informal. You can use your authority to help any quieter or lower-status guests participate equally.

- Connect people. Left alone, people tend to talk to those they already know or feel comfortable approaching. It’s also common—particularly in conferences—for people to put forward the best version of themselves and hide their authentic selves. People usually need some encouragement to make new connections or show vulnerability. As a host, you can also lead by example.

- Provoke good controversy. While it may feel safer to stick to positive topics and themes, particularly in professional settings, this creates a kind of phoniness. Parker argues that the common advice to avoid talking about sex, politics and religion is “epically bad”, and has caused countless mediocre and dull gatherings. The right controversy, in the hands of a good host, can add energy, life and authenticity to gatherings. Of course, not every gathering has to have controversy.

Example: Getting people to be authentic at the World Economic Forum

The World Economic Forum (WEF) might be one of the best examples of a networking event dominated by superficial networking and one-upmanship.

One year, Parker was invited to join a WEF council on new models of leadership, a few months before the major event in Davos. The WEF council held an earlier conference to surface ideas for Davos. Parker suggested throwing a small, intimate dinner the night before that earlier conference, with 15 people from various councils. They established clear rules for that dinner: each person would give a toast based on a personal story about what they think makes a good life, and the last person to volunteer would have to sing their toast.

Parker took the lead by sharing a vulnerable story about feeling truly seen. Other participants followed, dropping their rehearsed, professional scripts and personas. The singing rule kept things moving as it disincentivised people from waiting too long. Many prefaced their stories with statements like “I’ve never said this out loud before” or “I have no idea what I’m going to say”. It was a moving, beautiful, night. The evening went so well that Parker replicated the format at other events, calling it “15 Toasts”.

… [S]o often when we gather, we are gathered in ways that hide our need for help and portray us in the strongest and least heart-stirring light. It is in gathering that we meet those who could help us, and it is in gathering that we pretend not to need them, because we have it all figured out.

You may have to exercise your authority throughout the gathering, not just at the beginning. Rules and norms have to be continually enforced, else the gathering can easily go off-track.

Use your authority generously

Don’t use your authority for your own benefit, but in service of your guests and the gathering’s purpose. The authority is justified by the generosity.

True generosity sometimes requires being willing to be disliked in the short term to create a better experience for everyone. For example, shushing people who are speaking too loud or talking on their phones may incur the ire of those being shushed, while benefiting everyone else. Costs are concentrated, while the benefits are diffuse.

Sometimes generous authority demands a willingness to be disliked in order to make your guests have the best experience of your gathering.pibus leo.

In Parker’s experience, institutional gatherings are more likely to suffer from ungenerous authority, while personal gatherings are more likely to suffer from being too “chill”.

Use rules to create a temporary alternative world

The best gatherings transport us into a temporary alternative world with its own explicit rules, creating a space for people to behave differently from our normal lives. While gatherings with explicit rules might seem controlling, they can actually be more liberating.

Implicit vs explicit rules

Certain social circles will often have a common set of implicit norms and behaviours. Parker refers to these as “etiquette”. Etiquette works well in stable, homogenous groups, allowing people to coordinate with each other.

However, in today’s more diverse world, explicit rules are more inclusive and effective. Unlike etiquette, explicit rules are clear and can be learned instantly. They can also be created and removed quickly. “Pop-up rules” can be experimental, and give people social cover to behave in ways they wouldn’t normally.

If implicit etiquette serves closed circles that assume commonality, explicit rules serve open circles that assume difference. The explicitness levels the playing field for outsiders.

Example: Dîner en Blanc

Dîner en Blanc is a global dinner party series involving up to 15,000 guests in a single city. Guests come in pairs and have to follow strict rules—they must only wear white, bring their own tables, chairs, and picnic basket, and clean up after themselves. The location is kept secret until the last moment.

These rules create a magical shared experience. The event has now spread to over 120 cities around the world.

Explicit rules can increase presence and intimacy

Rules can counterbalance problematic norms and increase presence during the gathering. One important example is in combating modern distractions like phones. While etiquette might suggest it’s polite to put your phones away and focus on the people in front of you, people often felt antsy about not checking phones. Explicit rules tend to be more effective at getting them push past those feelings.

Example: Serving people Egyptian style

At one of Parker’s friends’ dinner parties, people sat next to others they didn’t know, and the food was served banquet-style in large bowls. The host explicitly instructed her guests to serve each other without worrying about getting served themselves. She explained this was how they did things in Egypt.

Everyone still ends up with enough food, but this small instruction helped nudge strangers into relationships of care.

Example: “I Am Here” days

Parker and a few friends created “I Am Here” days with clear rules:

- Be present for the entire day (10-12 hours)

- Turn off technology

- Engage fully with the group

- Have a single conversation at meals

- Be game for anything

Parker explains that spending 12 consecutive hours together produces fundamentally different interactions than three 4-hour meetings because you can only chitchat for so long. After a while, reality sets in, walls start to come down and conversation grows deeper. People would share stories that they wouldn’t otherwise bring up.

Since participants had to commit to the whole day, they had to give up on trying to find a better option or some form of distraction. These rules created a feeling that it was “enough” to simply be there and forced a level of presence and intimacy that is rare in our modern world.

Use structure to create good controversy

Good controversy is generative rather than destructive. It helps people examine what they truly care about, release tensions, and can lead to increased understanding. But good controversy rarely happens spontaneously—it needs deliberate design and structure.

Before introducing controversy, Parker suggests creating a “heat map” to understand what areas are most likely to generate strong emotions, and building a foundation of trust. Clear ground rules can carve out a safe space for the conflict, ensuring it doesn’t leak out in other (destructive) ways. Ideally, participants will input into the rules themselves, which increases their legitimacy and may prevent past problems from recurring.

When the controversy comes up, allow it to develop productively and resist the temptation to immediately cool it down. Check in with participants and the group about their emotional state to make sure things don’t spiral out of control and destroy trust. If done well, productive controversy can surface important truths and help groups move forward together on tense issues.

Open and close with intention

The gathering starts before guests arrive

A gathering begins when people first hear about it. Every gathering is a social contract loaded with expectations for both the host and the guests. Between the invitation and the event is an opportunity to manage those expectations. You should find ways to let guests know what they’re signing up for when they agree to attend. Unless you make expectations clear (particularly if you have unusual rules or expect guests to show vulnerability), people will feel resistant when they arrive.

A conflict resolution expert, Randa Slim, told Parker that 90% cent of what makes a gathering successful is put in place beforehand. For high-stakes gatherings like international dialogues, Slim might spend two years building relationships before the actual meeting. The scale of your preparation depends on how big of an ask you’re making of your guests. When people have to travel a long way to attend, you should put more care and attention into preparation.

Less formal, personal gatherings may not need as much prep, but you can still use invitations to prime the behaviours and expectations you want your guests to show at the gathering. Asking guests to reflect or prepare something small can make a big difference. Even the simple act of naming your gathering will affect how people perceive it. For example, instead of calling something a “meeting”, you might call it a “brainstorming session” to indicate that you’re expecting guests to participate and bring ideas.

Open with impact

The opening of a gathering is crucial—this is when attention is at its highest and will set the expectations for the rest of the event. Studies show that people can best remember the first 5%, the last 5%, and the climactic moment of a talk. Don’t waste your precious opening moments on “throat clearing” like thanking sponsors or logistics like parking instructions. Sure, every gathering has logistical demands. But you don’t have to lead with it.

Example: Personal Democracy Forum — brought to you by Microsoft

The Personal Democracy Forum hosts its annual conference in New York. The theme of the forum is that in a democracy, everyone can participate not just the powerful and well-connected.

Parker describes how jarring it was when, one year, the forum began with one of the founders turning the stage over to an executive from Microsoft, its sponsor, to speak first. That small act reinforced how money buys special access, undermining the very purpose of the conference.

Your opening should honour and maybe even shock your guests slightly (in a good way), and then bind them together into a tribe. This might involve taking time for everyone to greet each other or reaffirm why they are there. At the start of every Tough Mudder race, for example, each participant raises their hand and recites the Tough Mudder Pledge.

These principles can also be applied in a smaller way in less formal gatherings. For example, you could personally greet everyone at the door, set the table before guests come over to dinner, or prepare nametags that make people feel valued.

Close thoughtfully

Many hosts treat their gathering’s ending as an afterthought, letting it peter out instead of closing intentionally. But how you end a gathering is important, because the ending will shape how people remember your gathering. An abrupt or ambiguous ending can leave your guests feeling awkward and confused about when to leave.

The first step to closing well is accepting that your gathering will end—accepting its impermanence or mortality. For dinner parties, Parker suggests making a “last call”, similar to what bartenders do before closing. This signals that the end is approaching, giving guests time to prepare and resolve any unfinished business. That said, sometimes it is okay to let guests choose their own ending, and cultural differences can play into what you choose to do.

A strong closing consists of two distinct phases:

- Looking inward to reflect on what has happened and bond as a group for a final time; and

- Turning outward to prepare for re-entry into normal life.

Not all gatherings need a moment to pause and reflect, but many would benefit from it. The more different your gathering was from everyday life, the more important it is to create a clear ending that helps guests transition back to reality. Parker also suggests helping guests find a thread—e.g. a written pledge, or some physical memento—to remind them of the gathering later. Such threads can convert an impermanent gathering into a permanent memory.

Example: Seeds of Peace re-entry process

Seeds of Peace is a summer camp that tries to reduce conflict in the Middle East by bringing together teenagers from different conflict regions. Much of it is like a normal summer camp, with canoeing, arts, and games. But every day also involves in facilitated small-group conversations where the teenagers engage more deeply and try to understand each other’s views.

Three days before the end of the camp, counsellors begin preparing campers for re-entry into their normal lives. A key event is the “Color Games” where the teens are split into arbitrary team (e.g. Blue and Green) and given T-shirts to match. They then compete in various events against the other team, and the winning team is declared at the end.

Afterwards, the campers change back into their normal shirts, are asked to think about how quickly identities can be formed and how this relates back to society. During the final session on the last night of camp, counsellors guide small group discussions about how challenging going home can be.

Just as you shouldn’t open with logistics or a list of thank yous, don’t end with them, either. People’s eyes will glaze over when you’re following a script. If you want to thank people, do it as the second-to-last thing instead.

End with something meaningful and clear that connects back to the original purpose for your gathering. Draw a clear exit line—a physical or symbolic moment—to mark the official end. Even if you’re hosting a casual dinner with friends, walking them to the door instead of letting them see themselves out can make a difference. What distinguishes a forgettable gathering from one that leaves a lasting impression often comes down to how intentionally the host marked its end.

My Review of The Art of Gathering

I’ve organised very few gatherings in my life, mostly because I hate logistics. A career as a wedding planner would be my personal version of hell. I’ve never been too keen on large social gatherings either, probably because most of the ones I’ve attended have been rather laissez-faire and underwhelming as a result.

But, over the past year or so, I started organising a small, regular podcast club with a few friends. Around the same time, I started attending a local rationalist meetup where the host took a much more intentional approach to gathering than I’d seen before. The most striking example was that, before the meetup, she would pick all the grapes off a stem to serve up as a snack because she’d read that people were more likely to eat grapes that way. (Yes, we are just that lazy.) I was also surprised at how much of a difference it made when she did small things like having name tags, stopping people who tried to monopolise the conversation, and breaking larger groups up into smaller ones. I later learned that The Art of Gathering was popular in rationalist/EA circles and decided to check it out.

There’s a lot of great advice in this book, much of it challenging assumptions I didn’t even know I had. Taken as a whole, it can make hosting a gathering feel rather daunting, but it’s important to remember that the primary audience for this book are probably hosts who are far more experienced at hosting than I am. (I’m thinking the advice in The 2-Hour Cocktail Party might be more suitable for informal social gatherings.) Still, I think gatherings are important and that good gatherings are, unfortunately, all too rare. So I’ll keep some of Parker’s principles in mind as I try to do my bit in creating some better ones.

Let me know what you think of my summary of The Art of Gathering in the comments below!

Buy The Art of Gathering at: Amazon <– This is an affiliate link, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through it. Thanks for supporting the site! 🙂

If you enjoyed this summary of The Art of Gathering, you may also like:

9 thoughts on “Book Summary: The Art of Gathering by Priya Parker”

Great Summary.

Thank you!

I often find the timing of your summary releases quite serendipitous. As it happens, I’m organising a gathering tomorrow and will be implementing some of Parker’s thoughts. Thanks as always for being a gateway to ideas!

What a happy coincidence! Good luck with the gathering and I hope it goes well 🙂

Interesting, I’ve literally never thought about developing my “gathering” skills before, now I know that’s a possibility, one I might try.

Yeah, I’d never thought of it either until this past year. Loving your new podcast, btw! 🙂

Hosting gatherings, like public speaking, is one of those “sounds-good-to-do-in-theory” things for me, given I have little intuition of how to go about it. This might give me a little extra motivational (and informational) boost to start 🙂

Ha! You’re already ahead of me because for most of my life it didn’t sound good to me even in theory 😛 It’s only very recently that I’ve become more open to the idea that hosting gatherings might not be so bad… and maybe even rewarding!

Found your website today. Im impressed, than you!