My latest summary is for The New Map: Energy, Climate, and the Clash of Nations by Daniel Yergin, which explains how changes in energy markets are reshaping geopolitics.

Estimated time: 28 mins

Buy The New Map at: Amazon (affiliate link)

- Key Takeaways from The New Map

- Detailed Summary of The New Map

- Energy is a major driver of geopolitics

- The shale revolution has made the US into an energy superpower

- Russia uses energy to project geopolitical power

- China's heavy reliance on energy imports poses a key strategic vulnerability

- The Middle East's challenges in the energy transition

- The clean energy transition

- My Review of The New Map

Key Takeaways from The New Map

- Energy is a major driver of geopolitics.

- The shale revolution beginning in the 2010s has made the US into an energy superpower.

- Shale production combines hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) with horizontal drilling to extract oil and gas from previously inaccessible rock formations.

- America’s new energy abundance has reduced its strategic vulnerability and dependence on Middle Eastern oil, increased America’s influence in Asia, and reduced Russia’s leverage over Europe.

- Russia uses energy to project geopolitical power:

- Oil and gas exports fund nearly half of Russia’s government budget

- Much of Russia’s gas to Europe flows through pipelines in Ukraine, which is a source of conflict between the two countries.

- Russia has tried to bypass Ukraine by using alternative pipelines, but the US blocked one of these (Nord Stream 2) mere weeks from completion.

- Russia’s new energy alliance with China is part of its “pivot to the east”, which reduces its reliance on the European market.

- China’s heavy reliance on energy imports poses a key strategic vulnerability:

- China imports 75% of its oil, mostly via shipping lanes with vulnerable chokepoints like the Malacca Strait, which is part of why China wants control over the South China Sea.

- The Belt and Road Initiative is also driven by energy security, with many investments in energy projects and pipelines.

- The desire for energy security has also encouraged China to invest in renewables, especially solar panels and lithium batteries.

- The Middle East faces challenges in both the green energy transition and America’s shift away from the region:

- Countries like Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Iraq are heavily dependent on oil revenues. Saudi Arabia has tried to diversify away from oil, such as by publicly listing part of Saudi Aramco.

- When the shale revolution caused prices to fall in 2014, the OPEC countries joined with Russia to cooperate on boosting prices (“OPEC-Plus”).

- The discovery of major gas fields in the Eastern Mediterranean in 2009 has significantly increased Israel’s energy security.

- The world is now transitioning to clean energy but this will not happen overnight:

- Global energy consumption is still growing as emerging economies continue to develop. At a global level, the energy transition so far has been an energy “addition”—renewables are growing on top of traditional sources of energy, rather than replacing them.

- 3 major trends in transport could converge to dramatically reduce oil demand: electric vehicles, autonomous vehicles, and ride-hailing services. But challenges remain, and it takes a long time for fleets to turn over.

- Solar and wind are already cost-effective, but they suffer from intermittency problems so need to be supplemented. Further technological breakthroughs in carbon capture, energy storage, and hydrogen will likely be needed to achieve ambitious net zero targets.

Detailed Summary of The New Map

Yergin includes a lot of interesting historical background, especially for the Middle East, which provided some helpful context. However, since much of this history can be found elsewhere, this summary focuses on the parts that are more directly relevant to energy.

Energy is a major driver of geopolitics

Energy—particularly oil and gas—has played a major role in geopolitics and will continue to do so, even as the world transitions to renewable sources.

For more than a century, energy—its availability, access, and flows—has been intertwined with security and geopolitics. No other commodity has played such a pivotal role in driving political and economic turmoil.

Countries dependent on oil exports are at the behest of oil price volatility. Oil prices have triggered major political upheavals—high oil prices in the 1970s and 2000s helped Saddam Hussein and Vladimir Putin consolidate power, while a price collapse in 1986 contributed to the Soviet Union’s eventual dissolution.

Similarly, for countries dependent on oil imports, energy is a strategic vulnerability. A major driver behind China’s Belt and Road Initiative, its aggressive actions in the South China Sea, and its clean energy push is to secure energy supplies and reduce dependence on vulnerable shipping lanes.

In recent decades, the energy landscape has undergone dramatic shifts as the shale revolution took hold in the US. Power traditionally held by OPEC (the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) has now shifted to the “Big Three” energy exporters—the US, Russia, and Saudi Arabia. This was most clear during the COVID-19 crisis when these three powers agreed to historically large production cuts to prop up plummeting oil prices.

COVID-19 collapse in oil prices

When COVID-19 struck in early 2020, oil demand plummeted as travel and transportation ground to a halt. In March 2020, Saudi Arabia pushed for production cuts to stabilize prices, but Russia refused because it didn’t want to cede market share to the US.

With no deal reached, both countries ramped up production and flooded the market, at the same time the pandemic worsened. By late March, oil prices had collapsed to $14 per barrel. Thirteen US senators from oil-producing states wrote to Saudi Arabia complaining about its increased output and threatening to withdraw military support. President Trump then got involved to try and broker a deal.

As storage facilities filled up and oil reached a historic low of negative $37.63 on 20 April (albeit only in the futures market), the pressure for a deal became unbearable. OPEC-Plus finally agreed to a deal cutting production by 9.7 million barrels per day starting in May 2020—the largest oil supply cut in history.1The US didn’t agree to production cuts because under their federal system, that power lay with individual states and private companies, not the president. However, they pointed out that market forces would naturally curtail US production as low prices made new drilling uneconomical.

This deal marked a new era in global energy, with the US, Saudi Arabia, and Russia emerging as the “Big Three” in world oil markets.

The shale revolution has made the US into an energy superpower

The shale revolution fundamentally transformed America’s position in global energy markets. Hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) and horizontal drilling allowed the US to unlock vast reserves of oil and gas from previously inaccessible shale rock formations. The shale revolution started in 1998 with an explosion in natural gas output. In the 2010s, this technology was extended to oil, transforming the US from a net importer of oil to energy independent on a net basis.2The US still imports oil because its refining system is set up to handle low-quality, heavier crude oils, whereas shale oil tends to be higher-quality. So the US imports heavier oils from places like Canada, Mexico, Venezuela and the Middle East for refining, and exports shale oil.

The technology

Fracking is when you basically inject a blend of water, sand, gel and chemicals into rocks to break open tiny pores in order to get natural gas or oil out. Shale is “short cycle”—wells can start producing within 6 months for merely $7 million—so companies can respond quickly to prices. This is very different from traditional oil extraction, where projects can take 5-10 years to develop at costs ranging from hundreds of millions to billions of dollars. However, shale wells deplete faster and require constant new drilling, while traditional wells can last many years.

Fracking does come with environmental risks, including water contamination and increased risk of earthquakes. However, shale production is highly regulated at the state level and Yergin believes the environmental risks are manageable. Moreover, as fracking increases the supply of natural gas (which has lower carbon emissions), there are even environmental benefits. By 2019, America’s CO2 emissions had fallen to the levels of the early 1990s, even though the US economy had doubled since then.

Economic impact

The economic impact has been profound. Once a major energy importer, the shale revolution made the US into an exporter of both oil and gas (as liquefied natural gas or LNG). Yergin estimates the shale revolution reduced America’s trade deficit by over $300 billion in 2019. States like Texas and North Dakota saw direct booms, but jobs supporting shale activities were created even in states like New York that banned fracking.

Manufacturers from other countries including Europe, China and Australia began setting up facilities in the US to benefit from its cheap natural gas, which is used both as a fuel and raw material in making chemicals.

Geopolitical impacts

The abundance in energy has dramatically altered the US’s foreign policy options. Since WWII, with the post-war boom, the US has been a net importer of oil. In 1950, the US extended an explicit American security guarantee to Saudi Arabia to ensure its oil didn’t fall under Soviet control. A major reason for US involvement in the Middle East has been because of how important oil is to America’s allies, trading partners, and to the world economy more broadly.

But the shale revolution reduced the US’s dependence on Middle Eastern oil. By 2020, America surpassed Russia and Saudi Arabia to become the world’s largest producer of both oil and natural gas. Shale also allowed the US to extend its influence in Asia by supplying oil and gas to China, India, Japan, and South Korea.

Russia uses energy to project geopolitical power

With its vast oil and gas reserves, Russia is an energy and political superpower even though its economy is only slightly larger than Spain’s. It’s one of the “Big Three” oil producers and the world’s second-largest natural gas producer. Russia might have even more shale oil than the US—but it doesn’t have the same technical know-how that US shale producers do, so it doesn’t extract as much.

Vladimir Putin, who has a deep understanding of energy markets, has made energy central to his vision of restoring Russia as a great global power. Oil prices have also helped Putin consolidate power—although oil prices collapsed in 1986 and remained low during the 1990s, they recovered after Putin came to power in 2000. These high prices allowed Putin to pay off Soviet-era debts, raise wages and pensions, and modernise the military.

However, with oil and gas making up 30% of Russia’s GDP and funding 40-50% of its government budget, its dependence on energy exports also presents a vulnerability for Russia.

Russia, Europe and Ukraine

Europe depends on energy imports and is one of Russia’s main export markets. For a long time Europeans have debated the risks of importing energy from the Soviet Union and Russia. Western Europeans (particularly the Germans) generally welcome the imports while Eastern and Central Europeans more nervous about them.

Russian gas flows to Europe through pipelines in Ukraine. Those pipelines were built when Ukraine was still part of the Soviet Union, and Ukraine charges Russia tariffs for their use. But Ukraine is also dependent on Russia for energy imports. This mutual dependency has made for a volatile relationship. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia and Ukraine have argued over the prices of both Ukraine’s tariffs and Russia’s gas.

Relations between the two countries got worse after Viktor Yushchenko won the 2004 Ukrainian presidential election, beating out a more Russian-friendly candidate after the Orange Revolution. On January 1, 2006, Russia cut off gas supplies to Ukraine. It claimed this was because of a pricing dispute, but others saw it as political punishment. Ukraine responded by siphoning off gas meant for Europe. After a few days, the two sides managed to come to a new agreement.

A similar but more severe crisis occurred in January 2009, lasting over two weeks before the countries reached a new deal. This time, however, both Ukraine and Europe were prepared. They had built up storage reserves and no shortages occurred, despite the unusually cold winter.

Bypassing Ukraine with Nord Stream

To reduce dependence on Ukrainian pipelines, Russia invested $10 billion in the Nord Stream pipelines running under the Baltic Sea directly to Germany.

The original Nord Stream was completed in 2012 with limited opposition. But Nord Stream 2 began after Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, so was much more controversial—and not just in Europe. “Russia” had become a divisive topic in the US because of its interference in the 2016 US presidential election, and a group of 39 US senators argued that the pipeline would increase Europe’s susceptibility to Russian influence. When Nord Stream 2 was mere weeks from completion, the Trump administration sanctioned the Swiss firm that owned the pipe-laying barge and forced it to stop its work. Europeans were outraged by this, as they didn’t think Russian interference in US elections should affect construction of a pipeline in Europe.

Russia’s pivot to the East

Europe’s dependence on Russian gas has waned as global LNG production has boomed. Countries like Poland, once completely dependent on Russian gas, now have LNG import terminals that allow them to import LNG from over 20 countries. Ukraine, similarly, is no longer directly dependent on Russian gas. It has domestic production that supplies about two-thirds of its demand, and also imports from Slovakia, Hungary and Poland. Europe’s efforts to decarbonise and transition to renewables have also reduced its reliance on Russia energy. Unlike in the US where climate change is a politically polarising topic, strong climate policies are found across the political spectrum in Europe.

As its relationships with the West deteriorated, Russia has pivoted toward Asia. Russia is now China’s main oil supplier, and the two have entered into a $400 billion natural gas deal over 30 years. The countries have also partnered to build new oil and gas pipelines, such as the Eastern Siberia–Pacific Ocean (ESPO) oil pipeline and the Power of Siberia gas pipeline.

… [E]nergy is a very important part of this new geopolitical nexus. A relationship that was once based on Marx and Lenin is now grounded in oil and gas.

Russia has also invested in nuclear-powered icebreakers and ice-class tankers to undertake projects in the Arctic, as climate change makes transport and drilling increasingly viable. In August 2018, the first LNG cargo travelled from Russia’s new port city of Sabetta to China along the Northern Sea Route, which is about 30% shorter than the traditional shipping route from Europe to China. Though still a supplementary route, the Northern Sea Route has been welcomed by Japan, South Korea and especially by China.

However, Russia and China’s interests are not completely aligned. As China grows its influence in Central Asia, it challenges Russia’s dominance in the region. Major Chinese banks also complied with the Western sanctions on Russia for annexing Crimea, highlighting the limits of the Chinese-Russian partnership. The relationship is an asymmetrical one—for Russia, China represents 11% (and growing) of its total exports, but Russia accounts for merely 2% of China’s exports. Economically, the West is much more important to China than Russia is.

China’s heavy reliance on energy imports poses a key strategic vulnerability

China’s economic growth requires enormous amounts of energy. Today, China represents almost 25% of world energy consumption—more than any other country.

Energy security and the South China Sea

Apart from coal, China has few domestic energy sources. Around 75% of China’s oil is imported. Most of those imports have to pass through the narrow Malacca Strait in the South China Sea, which is a large part of why China wants to control that area.3Other reasons include access to natural resources like oil and fisheries. But the South China Sea is also crucial for other countries, particularly Japan and South Korea, with 30% of all global trade passing through it. The South China Sea is a source of great tension between the US and China.

The Belt and Road Initiative

In 2013, Xi Jinping launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), an ambitious infrastructure project aimed at connecting China with Europe, the rest of Asia, the Middle East and Africa. Somewhat counterintuitively, the “Road” refers to sea routes (the Maritime Silk Road), while the “Belt” refers to the railways, roads and pipelines connecting China and Europe via Central Asia.

A key driver of the BRI is energy security, with the bulk of investments in Central Asia going into energy projects and pipelines. To date, the single biggest project is the $62 billion China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, around 70% of which is for electric power-related investments. A notable part of this project involves developing a deep water port at Gwadar which, combined with overland routes in Pakistan, gives China’s imports and exports a path that bypasses the Malacca Strait.

Other countries are nervous about the increasing soft power associated with China’s BRI. The US established its own International Development Finance Corporation in response, with $60 billion of lending capacity to match China’s Silk Road Fund. India is one of the countries most concerned about the BRI, especially China’s involvement in Pakistan, as it worries about becoming encircled. And while Russia seems to be okay with the BRI for now, it still sees Central Asia as being within its sphere of influence and may grow worried if countries in that area keep getting closer to China.

Clean energy transition

While Xi Jinping announced in 2020 China’s goal of reaching net zero carbon by 2060, its overall energy mix is dirtier than the US’s:

- Coal makes up almost 60% of total energy (vs 11% in the US);

- Oil makes up about 20% (vs 37% in the US); and

- Natural gas makes up just 6%, but is growing fast (vs 32% in the US).

[The figures have changed since 2019/2020, but not by much. The main difference is that coal in China fell to about 53% in May 2024.]

However, China has moved aggressively to secure its position in clean energy, particularly solar power and electric vehicles (EVs). Promoting clean energy helps China in several ways: it reduces air pollution, increases energy security, and increases its competitiveness in automotive manufacturing. Since China was a latecomer to auto production, it didn’t stand much chance of becoming competitive in the conventional car market.

During the 2010s, German and Chinese government subsidies for renewable energy have combined to help bring down the costs of solar by around 80%. Between 2010 and 2018, China’s solar-cell manufacturing capacity rose 5x, outstripping the increase in demand. As prices plummeted, some Chinese companies went bankrupt. But the Chinese government then stepped in to grow the domestic market for solar production. China now produces around 70-80% of the world’s solar panels and almost 60% of the key raw material, polysilicon, which gives it a strong position in the solar supply chain.

EVs have also been growing quickly in China, which is now the largest auto market in the world, thanks in part to government intervention. In addition to setting quotas for manufacturers, the government has also created incentives on the demand side like with license plates. China also manufactures almost 75% of the world’s lithium batteries, which gives it an advantage in EV production.

Example: License plates for EVs

A car has to have a license plate before it can be legally driven on public roads. However, to manage congestion, license plates in China are rationed and given out via a lottery system. In large cities, the odds of winning a license plate are pretty low (e.g. 1 in 907 in Beijing) and you have to pay a rather hefty fee as high as $13,000 for the license even if you win.

But there is an exception for EVs, which automatically receive license plates without having to pay the license fee. This has significantly boosted demand for EVs in China. In 2019, more than half of all EVs sold in the world were sold in China.

The Middle East’s challenges in the energy transition

The Middle East’s economy depends heavily on oil and gas exports. For the major producers—Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Iran, and Iraq—oil is central to their national budgets and development plans. Even minor producers like Syria and Yemen rely on oil revenues to prop up repressive regimes.

After WWI, countries recognised oil as a strategic commodity, which influenced how the British and French drew up the Middle East’s boundaries in the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923. More recently, there have been some significant shifts in energy that are changing the Middle East:

- the shale revolution has reduced the West’s reliance on the Middle Eastern oil;

- discovery of gas fields in the Eastern Mediterranean is changing Israel’s power; and

- Saudi Arabia is diversifying away from oil because of the coming energy transition.

Yergin also covers many of the conflicts in the Middle East, such as the Arab Spring, the Iraq wars, the Syrian and Yemen civil wars, and the Saudi Arabia vs Iran rivalry in a fair bit of detail. Most of this doesn’t relate to energy, so I’ve omitted it from this summary.

The shale revolution

The US shale boom threatened the Middle East’s oil revenues and and altered the region’s strategic importance to the West. Throughout 2011 and 2013, oil prices had been pretty stable at around US$100 per barrel. The shale boom had already started, but the increased oil supply was offset by supply disruptions in Libya, Nigeria, and Venezuela, as well as the international nuclear sanctions on Iran. But beginning around 2014, the downward pressure on prices from the shale boom began to dominate and oil prices started falling. Producers grew alarmed. By mid-November, the price dropped to $77. Many long-cycle oil projects that had been planned around a $100 barrel price had to be postponed or cancelled.

OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) met several times to discuss a coordinated agreement to cut supply and raise prices, but Saudi Arabia was reluctant to cut production because of its rivalry with Iran. (Iran stood to gain the most from high oil prices because sanctions limited how much it could export.) Moreover, neither the US nor Russia were part of OPEC. If OPEC cut production but the US and Russia didn’t, they would benefit from higher prices at OPEC’s expense.

In 2015, prices dropped below $30 a barrel. Many US shale producers went bankrupt, and the remaining ones became more efficient. Oil producing countries grew increasingly desperate, with Russia and Saudi Arabia drawing down on their sovereign wealth reserves. Iraq saw its government revenues fall by 50%. Venezuela even suggested organising environmental campaigns inside the US to protest shale!

In October 2016, OPEC and a group of 11 non-OPEC countries led by Russia finally agreed on a deal, which became known as “OPEC-Plus”. The deal did not include the US, but US output had fallen anyway as many shale producers got hit by the low prices. Besides cooperating on oil, Russia and Saudi Arabia also signed agreements on investments, military matters, weapons, and technology. For Russia, this cooperation helped deepen its influence in the Middle East. For Saudi Arabia, this gave it more options as its relationship with the US grew increasingly strained.

Discovery of gas in the Eastern Mediterranean

Israel historically imported all its energy, creating strategic vulnerability. But in 2009 and 2010, major gas discoveries off Israel’s coast—Tamar and Leviathan—have transformed its energy security. True to its name, Leviathan is one of the largest natural gas fields in the world. Today, Israel generates over 60% of its electricity from domestic natural gas and has begun exporting to Egypt and Jordan. It could even become an international exporter to Europe.

Cyprus and Egypt subsequently discovered significant gas fields in their own waters—Aphrodite and Zohr, respectively. These discoveries have created new geopolitical tensions, particularly with Türkiye, which disputes the maritime boundaries. Plans for an undersea pipeline (the EastMed) to send the gas to Europe have stalled due to these disputes.

Saudi Arabia is diversifying away from oil

Saudi Arabia is the world’s largest oil exporter. Because it’s the only country with significant “spare capacity”—its oil wells can be brought online quickly to balance global markets—Saudi Arabia is sometimes called the “central bank” of oil. Oil directly accounts for over 40% of Saudi Arabia’s GDP and 60-90% of government revenues. But even non-oil activity is highly dependent on things that are financed by oil revenues.

In 2016, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman launched “Vision 2030” in a bid to diversify the economy and make it more entrepreneurial, competitive and high-tech. As part of this shift, Saudi Arabia floated 1.5% of Saudi Aramco—its national oil company—in the largest initial public offering (IPO) in history. Proceeds from the IPO went to Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund to fund Vision 2030 and other non-oil investments.

Still, diversification has proven difficult. Leaders have always said they wanted to diversify away from oil, but it’s easier said than done. Not only does the presence of oil promote rent-seeking and corruption, it can also crowd out entrepreneurship in other sectors. Oil exports also increase the country’s currency, making it harder for non-oil exports to compete.

Experience proves how hard it is to diversify away from overdependence. It requires a wide range of changes—in laws and regulations for small and medium-sized companies, in the educational system, in access to investment capital, in labor markets, in the society’s values and culture. These are not changes that can be accomplished in a short time. In the meantime, the flow of oil revenues creates a powerful countercurrent that favors the status quo.

The clean energy transition

The transition will take time

The world is now gradually transitioning to clean energy. The global oil and gas industry is worth around $5 trillion and supplies almost 60% of world energy. Oil and gas are also essential for chemicals and plastics, and demand for those grows faster than GDP. There are also likely to be bottlenecks as the world moves from a fuel-intensive system to a mineral-intensive one. While the top three oil producers control only 30% of production, the top three lithium producers control over 80% and countries are now focusing on securing battery supply chains. For at least the next few decades, oil will remain a significant part of the global energy system.

Previous energy transitions haven’t been fast, either. The shift from wood to coal began in Britain in the 13th century but it took around 700 years before coal supplied half of the world’s energy. The shift to oil was, thankfully, considerably faster—after oil was discovered in 1859, it overtook coal globally in about 100 years.

So far, the energy “transition” has really just been energy addition, with renewables growing alongside fossil fuels rather than replacing them. Coal is still a key source of energy for both China and India.

Transportation — 3 converging trends

Transportation accounts for about a third of global oil consumption, with cars making up about 20% of that total. Three converging trends could reduce this significantly:

- Electric vehicles (EV). These are becoming increasingly mainstream, yet they still rely heavily on government regulations, subsidies and other incentives. Yergin is not sure they will remain viable without subsidies, and mass-market adoption would be too expensive for governments to subsidise.

- Autonomous vehicles. If perfected, it could dramatically reduce costs for ride-hailing services and further erode personal car ownership. However, while the technology continues to advance, full self-driving remains challenging.

- Ride-hailing services (e.g. Uber, Lyft, and China’s DiDi). These reduce the need for people to own their own cars, potentially allowing for more efficient vehicle use. However, they may also increase total miles driven by diverting trips from public transport.

There’s no guarantee these 3 trends will converge, but there could be valuable synergies if they do. Autonomous vehicles and ride-hailing combined could eliminate the biggest cost for ride hailing—the drivers. Each car could be used more efficiently, roaming the road both day and night. Such vehicles could well be electric because, despite their higher upfront costs, EVs tend to have lower operating costs than gasoline cars.

However, various challenges remain:

- Existing fleets of cars do not turn over quickly. In the US, cars remain on the road for around 12 years on average, and new car sales represent only about 6-7% of the total fleet.

- Autonomous vehicles are very expensive. Yergin estimates at the time of writing that the technology to make a car autonomous adds about $50,000 to its production cost. But with scale and technological advancements, that premium might fall to only $8,000 to $10,000. [We’re still far above that $8-10k premium, and it seems like even the $50k premium was a conservative estimate.]

- Trucks, ships, trains and airplanes still rely on oil. The number of civilian airliners globally is expected to double by 2040 as the middle class grows richer in emerging economies—over 80% of the world’s population has still never flown. Even if we found a good alternative to jet fuel, it would take a long time to have an impact given the lifespans of existing planes.

Technologies needed

The path forward will require a mix of approaches. Though solar and wind are already cost-effective, they are intermittent and don’t always provide enough energy at peak consumption periods. The problem is storage—unlike oil in tanks or gas in caverns, we don’t yet have ways to store renewable energy efficiently. Large-scale battery development could provide the breakthrough needed. In the meantime, natural gas can complement intermittent solar and wind.

Natural gas is particularly useful in developing countries where 3 billion people still don’t have access to clean cooking fuels, and a billion don’t have electricity. It’s a much cleaner fuel than alternatives like coal, wood, and crop waste. Some major energy companies are now calling themselves “gas and oil” companies, recognising the growing importance of gas.

Others are going broader into in branding themselves “energy companies” and investing in new technologies such as hydrogen, which has the potential to make up 10% or more of the world’s total energy. Nuclear, carbon capture, and advancements in batteries would also help with the energy transition.

My Review of The New Map

The New Map was a very interesting book about a topic I knew very little about. I’d never previously thought about energy security and how it intersects with geopolitics—but of course it does.

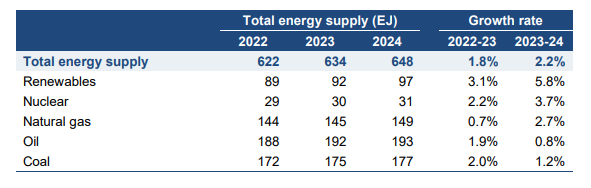

I wasn’t a huge fan of Yergin’s writing, which relied a bit too much on narrative and got rather repetitive towards the end. Since I don’t have a background in energy, I wish he would’ve spent more time putting figures into context instead of just sprinkling them throughout the book. For example, I looked up the IEA’s Global Energy Review 2025 and found the following table:

This table, which post-dates Yergin’s book, clearly show how total energy demand is increasing in absolute terms, even as the share of renewables is growing. But Yergin doesn’t use tables or graphs throughout the book, instead opting for a rather scattershot approach to statistics. What makes things even worse is that he doesn’t give sources for most of his claims, making them hard to verify and update.

The lack of sources was especially frustrating when he discussed the energy transition, where things are changing quickly. For example, Yergin wrote that EV adoption was still low, making up less than 3% of new car sales worldwide. But shortly after The New Map was published, adoption rates soared in both Europe and China. By 2024, the EV share of new car sales had grown to 22% worldwide (and a whopping 48% in China)! (source: IEA).

I don’t know enough about this topic to judge whether Yergin has been overly pessimistic about the energy transition or merely realistic. I appreciate that it’s hard to make predictions, especially in fast-moving spaces, and it’s been around half a decade since Yergin wrote The New Map. Despite some quibbles, I found the book to be a fascinating and worthwhile read—I’d just place more weight on the chapters about history and geopolitics than on the ones about the energy transition.

Let me know what you think of my summary of The New Map in the comments below!

Buy The New Map at: Amazon <– This is an affiliate link, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase through it. Thanks for supporting the site! 🙂

If you enjoyed this summary of The New Map, you may also like:

- Not the End of the World by Hannah Ritchie, which debunks a lot of myths and offers some reasons for optimism about our environmental problems.

- Prisoners of Geography by Tim Marshall, which explains how geography affects geopolitics and many differences between countries.

- Destined for War by Graham Allison, which discusses the rivalry between America and China and, despite its name, argues that a great power war is not inevitable.

- 1The US didn’t agree to production cuts because under their federal system, that power lay with individual states and private companies, not the president. However, they pointed out that market forces would naturally curtail US production as low prices made new drilling uneconomical.

- 2The US still imports oil because its refining system is set up to handle low-quality, heavier crude oils, whereas shale oil tends to be higher-quality. So the US imports heavier oils from places like Canada, Mexico, Venezuela and the Middle East for refining, and exports shale oil.

- 3Other reasons include access to natural resources like oil and fisheries.

2 thoughts on “Book Summary: The New Map by Daniel Yergin”

I always find it fascinating to hear geopolitics broken down like a game: who are the players, what cards do they have, etc. It’s a good exercise in understanding (that has the added benefit of increasing empathy to other nations). Like, it’s so interesting to contrast Saudi Arabia (which has been heavily reliant on oil demands) to Taiwan’s strategic importance, which is purely technological. What books have been your favorite in this genre?

Honestly, I am still such a novice in this area I’m not sure my recommendations will be all that valuable. Books about geopolitics can have so many different angles, and I’m not well-versed enough to be able to reliably spot biases and unfair slants. So this is an area where you have to read broadly (and skeptically) in order to form good views.

I enjoyed The New Map because it made me see geopolitics from an angle I hadn’t previously considered. Destined for War was also a good read – I found the previous examples of rising powers and ruling powers quite enlightening (but I think the name of the book is misleading and arguably harmful). If you like the game theory aspect, I’d recommend Why We Fight – it’s less focused on geopolitical disputes between actual countries, but gives a good framework for understanding why wars happen at all and why peace deals can be hard to reach. The Lines on Maps YouTube channel is also good at applying game theory frameworks to disputes happening now – the guy is a professor at the University of Pittsburgh and seems to know what he’s talking about.