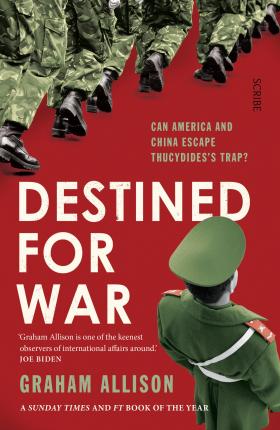

This summary of Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’ Trap? explains the dynamic that arises when a rising power threatens an existing ruling power. Graham Allison looks back at examples of similar past dynamics starting with Athens and Sparta, and suggests ways in which we can learn from history and hopefully avoid war.

Buy Destined for War at: Amazon | Kobo (affiliate links)

- Key Takeaways from Destined for War

- Detailed Summary of Destined for War

- Athens and Sparta (WAR)

- America and China

- Japan and the US (1899 to 1941) (WAR)

- Germany (Prussia) and France (1800s) (WAR)

- Britain and Germany (1900s) (WAR)

- Spain and Portugal (1400-1500s) (NOT WAR)

- Germany and Britain and France (1990s) (NOT WAR)

- America and Britain (1900s) (NOT WAR)

- Soviet Union and the US (1940s-1980s) (NOT WAR)

- Other Interesting Points

- My Thoughts

Key Takeaways from Destined for War

- Thucydides’ trap refers to the dynamic where a rising power threatens to displace a ruling power. Thucydides was a Greek historian from Athens who wrote about the Peloponnesian War. In that war, Athens was the rising power and Sparta was the ruling power.

- In the course of history, there have been 16 cases where a rising power posed a threat to a ruling power. Only 4 of those cases did not result in a war. Allison covers a selection of the 16 cases in Destined for War, including all the ones that did not lead to war. Most (not all) of these are summarised below.

- America is the current ruling power and China is a rising power. China will eventually overtake America. This will be a huge disruption to the current global world order and is likely to result in a war between the two powers.

- The rising power often sees its rise as “benign”. As its confidence and pride grows, its sense of entitlement and demands for respect also grow. The ruling power sees the rising power’s demands as “ungrateful”. After all, the ruling power presided over the conditions that enabled the rising power to grow. The ruling power also fears the rising power, and feels insecure that its position as the ruling power may be usurped.

- Neither side may want a war, since the costs of war may far outweigh the benefits to both powers. But the triggers for a war are not always within the Governments’ control.

- The trigger may be a relatively minor thing that would not have caused much of a problem were it not for the underlying power dynamics. Allison argues that more important than the proximate “spark” that triggers a war are the underlying structural factors that lay the foundations for war.

- Alliances come with risks that may force a country into war – e.g. Sparta’s alliance with Corinth (see below). A country’s interests will not be completely aligned with those of its allies. Allison suggests that States tend to exaggerate benefits of alliances, and underestimate the risks of them.

- Another reason that states may repeatedly fail to act in what appears to be their own national interest is because of necessary domestic compromises within their government.

- Nuclear war is a like the game of “chicken” that reckless teenage boys play. If neither side turns away, both die. But if one side turns away too fast or too eagerly, they will be at the mercy of the more reckless side. Countries therefore have to bluff and maintain a degree of ambiguity.

- Clausewitz coined the term “fog of war” to refer to the uncertainty involved in a war.

- One country can misinterpret the other side’s actions. An effort to de-escalate could be misperceived as being escalatory.

- Countries will tend to focus on each other’s capabilities, since they don’t know what the other’s intent is. So even if one country decides to build up its military for defensive reasons, the other country may perceive it as being a threat.

- Allison has some suggestions for how America might avoid a war with China.

- Face up to the realities of the situation. Allison writes, “Strategy insists that diagnosis precedes prescription”. Both countries need to accept that war is not just possible but much more likely than currently recognised. But US should also recognise that there is no “solution” to China – it is a condition that must be managed over the long term.

- Examine all options and accept that there may be trade-offs. For example, could America give China some concessions on Taiwan in return for concessions in the South China Sea or vice versa? Or should America seek to actively undermine China by training and supporting separatists? Allison points out that China and US also have joint vital interests in limiting climate change, avoiding nuclear Armageddon or anarchy, and reducing global terrorism. They could work together on some of these.

- Devise an actual, long-term strategy. American policy on China at the moment consists of grand aspirations rather than reasonably achievable goals. The US is basically just trying to cling to the status quo and hoping it will work.

Detailed Summary of Destined for War

Allison noted 12 examples where the rising and rulings powers went to war. The four that he focused on in the book were:

- Athens and Sparta;

- Japan and the US;

- Germany (Prussia) and France; and

- Britain and Germany.

The four cases where war was averted were:

- Spain and Portugal;

- Germany and Britain and France (in the 1990s);

- the US and Britain; and

- the Soviet Union and the US.

From these four cases, Allison suggests some “clues for peace”.

Athens and Sparta (WAR)

It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war inevitable.

Thucydides, Greek historian

Sparta

- Sparta had a very “military” culture. The society prized military values such as courage and discipline. It only allowed physically perfect babies to live, and took sons from their families at a young age to enroll them in military academies. Men were not exempt from military service until the age of 60.

- Sparta was quite insular. It was not concerned with states far away and, unlike Athens, did not try to persuade others to follow their model. Rather, Sparta was more focused on preventing a Helot rebellion at home and retaining its dominance over the region. (The Helots were their slaves, and outnumbered Spartans 7-1.) Sparta was focused on preserving the status quo.

Athens

- Athens, on the other hand, was an open society. It had students from across Greece. It had no qualms about interfering with other states, toppling their governments and installing democracies. Athens believed they were at the cutting edge of human achievement.

- Athens’ economy was very strong and it had a lot of maritime trade links. It also had a large navy – more than twice the size of its nearest rival. Athens built a maritime empire of sorts, with colonies paying it for protection. But it saw its rise as completely benign, because it did not build its empire through violence.

- Athens felt it had played a key role defeating the Persians. It wanted to be recognised as a leading power in Greece.

The Wars

- In 490 BCE, a Persian invasion forced the Greeks to come together to face a common threat. There were a series of conflicts and minor wars during the First Peloponnesian War in 460-445 BCE.

- In 446 BCE, the two states signed a treaty, the Thirty Years’ Peace. The aim was to prevent more wars. But this treaty did not resolve the underlying tensions between Athens and Sparta – it just put them on hold.

- The great war between Athens and Sparta was the Second Peloponnesian War, which took place between 431-404 BCE.

- The Second War was started by a conflict between Corinth (a key Spartan ally) and Corcyra (a neutral power). Corinth built up the second largest navy in Greece (second to Athens), so Corcyra approached Athens for help.

- Athens didn’t really want to help because they didn’t want to risk violating the Thirty Years’ Peace. But at the same time, they didn’t want Corinth to take over the Corcyraean fleet because that would give Sparta more naval power. The Athens assembly debated the choices for two days. Ultimately, Athens decided to send a small symbolic fleet to Corcyra but the fleet would not engage unless attacked.

- The Corinthians felt outraged and turned to Sparta for help. Sparta was also torn. They didn’t want to antagonise Athens but also felt they needed to help their centuries-old ally, Corinth. If they didn’t help, then other Spartan allies may also feel like Sparta is not dependable, and wouldn’t help Sparta keep down the Helot threat at home.

- The Spartan king, Archidamus II, and Athens’ “First Citizen”, Pericles, were also personal friends. Archidamus could sympathise with Athens’ position and urged his people not to demonize the Athenians. But the Spartan hawks disagreed and the Spartan Assembly voted for war.

- Neither side had a clear military advantage and both were overconfident about their own abilities. The war was devastating for both and lasted for almost 30 years, ending the golden age of Greece. Sparta ultimately won but at enormous cost.

America and China

China

Economic Growth in China

- Allison cited a lot of impressive statistics about Chinas’ growth:

- China’s share of the global economy will grow from 2% in 1980 to 18% in 2016, and projected to be 30% in 2040.

- For every 2-year period since 2008, the increment of growth in China’s GDP has been larger than the entire economy of India.

- Even at its lower growth rate in 2015, China’s economy created a Greece every 16 weeks and an Israel every 25 weeks.

- Since 1980, China’s economy has grown at 10% a year on average.

- Today (i.e. 2017), Chinese workers are 1/4 as productive as American workers. If over the next decade or two they become half as productive as Americans, China’s economy will be twice the size of the US economy.

- Since the Great Recession, 40% of all growth in the world has occurred in China.

- By 2005, China was building the square-foot equivalent of today’s Rome every two weeks.

- Between 2011 and 2013, China used more cement than the US did in the entire 20th Century.

- Allison compares a bridge near Harvard that has been under construction for 4 years. In 2015, China replaced the substantially larger Sanyuan Bridge in 43 hours.

- The most recent Stanford University comparison of students entering college in computer science and engineering found that Chinese high school graduates have a 3-year advantage over American high-school graduates in critical thinking skills. [This seems surprising to me. Would be interested in the results of graduates in other fields and other skills measured.]

- Lee Kuan Yew, the founding father of Singapore, spent a lot of time with Chinese presidents, ministers, and other leaders. Every Chinese leader from Deng Xiaoping to Xi Jinping respected him greatly. Allison thought that Lee had some very useful insights on China, for example:

- “The size of China’s displacement of the world balance is such that the world must find a new balance. It is not possible to pretend that this is just another big player. This is the biggest player in the history of the world.”

- On a per capita level, China is still obviously far behind the US. At the time of the book’s writing, China’s GDP per capita was less than 1/5th the US’s [that still seems true today, based on 2020 figures].

One Belt, One Road

- One Belt, One Road (OBOR) is an enormous infrastructure project that China intends will connect Europe and Asia. It spans decades and will cost several trillion dollars.

- OBOR will increase China’s sphere of influence as it will drastically shorten the time needed to get between Europe and Asia (and places within Asia). For example, it currently takes a train one month to go from Rotterdam to Beijing. OBOR should shorten that to two days.

- One of the side benefits of OBOR is that it maintains demand for China’s construction, steel and cement industries, which had been flagging in recent years as China completed its high priority infrastructure projects.

China’s rising power syndrome

- Like Germany before WWI, China feels that it unfairly lost out because the rules of the global order today were made while China was weak and absent from the world stage.

- China’s demands for respect are likely stronger than historical examples of other rising powers. Unlike the other examples of “rising powers”, China has already had long periods where it was the “ruling power”. It feels particularly aggrieved from its “century of humiliation” at the hands of Western powers during the period from 1839-1949 (e.g. the Opium Wars, the loss of Hong Kong, Macau, parts of Manchuria, Taiwan and Dalian, the Eight Nation Alliance against the Boxer Rebellion, WWII).

- This grievance is not just felt by the Chinese government but by its population. The Communist Party emphasises that history to promote nationalism and unity (see also Tribe by Sebastian Junger). The Party’s core claim to legitimacy is that it “saved” China from falling to these foreign powers and, by making China stronger, will prevent a repeat of the century of humiliation. Most people in China therefore feel that political freedoms aren’t as important as having China be “great again”.

Foreign relations

- Confucianism does not like the idea of using physical coercion to achieve one’s goals. So China saw its military as a last resort.

- China’s traditional foreign relations approach was very similar to the way it ordered itself internally – hierarchical and orderly. And, unlike America, China never wanted to spread its cultural values universally.

- In 1793, during the reign of Qianlong, Lord Macartney arrived in Beijing as the envoy of King George III. He sought to establish diplomatic relations between Britain and China. Britain had thought China was a backward country and that Britain was doing China a favour.

- But the Chinese had no idea who he was and didn’t understand what he wanted – China had not had “diplomatic relations” with another country before. It didn’t even have a foreign ministry. The emperor rejected all of Macartney’s proposals. He allowed foreign merchants to continue trading in Canton, because he recognised that the tea, silk and porcelain produced by China was so important to Europe. In other words, China thought it was doing Britain a favour.

Chinese Military

- While all great powers have strong militaries, for China it is especially important because of its century of humiliation.

- China recognises that it made a historical mistake in ignoring the oceans. As a result, Xi has focused on strengthening the naval, air and missile forces of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), while reducing ground forces.

America

- Americans today grew up in a world where the US was always number one. Many Americans think of economic primacy as an inalienable right – it is part of the national identity.

When the US was a rising power, it was also belligerent

- The US started coming to power around the turn of the 19th Century. When TR Roosevelt joined President McKinley’s administration in 1897, he was very eager to build up the US navy and expand America’s territories and influence. He believed strongly that American dominance was its “Manifest Destiny”.

- Over the next 10 years, the US declared war on Spain and acquired Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines; threatened Germany and Britain with war; and supported an insurrection in Colombia in order to build the Panama canal, which benefited the US enormously:

- TR Roosevelt was eager for war with Spain since Spain held Cuba, which was so close to the US. The US quickly defeated Spain in the Spanish-American War of 1898 and they signed a peace treaty. Under that treaty, Cuba gained its independence and Spain ceded Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines to the US.

- TR Roosevelt insisted that interfering in other countries would improve the lives of people in those countries. He justified the US occupation of Philippines by claiming its people were living in “barbarism” and that the only way to free its people was to “destroy barbarism itself”.

- In 1902, Germany (supported by Britain and Italy), imposed a naval blockade on Venezuela because it had refused to pay its debts. Allison says that TR Roosevelt issued an ultimatum to Germany, threatening war if it did not defer to the US. [However, Wikipedia’s article about this Venezuelan crisis says that whether Roosevelt actually did this is debatable.]

- TR Roosevelt had long wanted a canal through Central America. A canal would benefit America greatly because then US warships wouldn’t have to go all the way around South America to protect its interests on the other side of the country. To get the canal, the US supported Panama’s independence, to the point of threatening the Colombian government. Once Panama got its independence, the US quickly got a treaty giving them rights to control the canal in perpetuity for a pittance. For example, Panama only got $250k per year from the canal while the US earned millions (by the time the canal was transferred back to Panama under President Jimmy Carter, it was around $540m).

- The US navy intervened in Latin America 21 times over 30 years between the announcement of the “Roosevelt Corollary” in 1904 and Franklin Roosevelt’s “Good Neighbour Policy” in the 1930s. (Unlike TR Roosevelt, FDR opposed excessive interventionism in Latin America.)

Similarities and differences between America and China

- Allison says that one thing America and China have in common is their “extreme superiority complexes”. Each sees itself as exceptional, without peers.

- Allison suggests that China’s superiority complex may be even stronger than the US’s. Traditionally China saw itself as the unique link between humans and the heavens. Harry Gelber explains that China didn’t think of there being a “China”, as in a country or civilization, at all. It just saw the Han people and everyone else was a barbarian. [This is from a long time ago though, before the world was so interconnected. It’s also probably exacerbated by the fact that China didn’t bother to explore much beyond its borders. I suspect Britain and other Western powers probably thought similarly about the aboriginal peoples they colonised.]

- America and China differ in how they view a government’s legitimacy:

- America sees democracy as the only legitimate form of government. The legitimacy of any government is derived from consent from those governed.

- Most Chinese would disagree – they believe legitimacy comes from competency and performance.

- America and China differ in how they view their own values:

- America believes its values, such as human rights, democracy, rule of law, individual freedoms, are universal. It therefore seeks to promote them in other countries (Samuel Huntington, a political scientist, has referred to the US as a “missionary nation”). Henry Kissinger pointed out that this view implies that governments in societies without these principles are not fully legitimate.

- China does not try to export its values. It’s content to let others look up to its values and admire them, or even attempt to copy them. But China doubts that others would be successful because it sees itself as unique.

- America and China differ in how they view their own identities:

- America is a nation of immigrants. Anyone can be an American.

- But to be Chinese, you have to be born Chinese. This also goes the other way – if you are of Chinese descent, you are Chinese even if you grew up in a Western country.

- America and China have different time horizons:

- The country of America is less than 250 years old. The US political system also tends to require US leaders to take prompt action to the problems of today.

- China consider its history is 5,000 years old. As a result, they are more patient in letting things be resolved at a later time. For example, Deng Xiaoping effectively put the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands issue on hold for a generation. Chinese also believe that many problems can only be “managed”, not solved, and that each course of action may yield new problems.

- America and China’s governments are different:

- China’s power and resources are concentrated in government. It can also make decisions with a focus on a longer timeframe (e.g. over a decade) because of the stability in government. Society is organsied by a strict hierarchy with the Chinese government at the top—Confucius’s first commandment is “Know thy place”. Hierarchy keeps order, which is the Chinese’s central political value. Allison points out that liberty, as Americans understand it, would upset this order.

- America’s system of “limited government” contains checks and balances against government power. The separation of powers between the executive, legislative and judicial branches is designed to achieve this, at the cost of delay and even dysfunction.

Different conceptions of world order

- Allison suggests that the key difference between the US and China (for purposes of the Thucydides Trap) is their different conceptions of world order.

- China believes in harmony and order through hierarchy (same as the way it orders itself domestically). Allison describe China’s strategy as “unabashedly realpolitik”. This allows the Chinese government to be very flexible without feeling any need to justify its behaviour.

- America’s view is conflicted. They want an international “rules-based” order, with rules that conform to its own domestic rules. But they also have a realpolitik understanding of “might is right”.

- The Chinese are sceptical of the US’s rules-based international order. They point out that those international rules were made when they were absent from the world stage.

- After WWII, the US led the way in creating the international institutions that advantage the US: the IMF, the World Bank, and the GATT (later the WTO). The US is the only country that has a veto power in the IMF and in the World Bank.

- When the World Bank refused to give China a larger share of the votes at the World Bank, it created its own Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). A lot of countries signed up to this (despite US pressure not to) because of how much capital China had. Before the AIIB was even established, the China Development Bank had passed the World Bank to become the biggest financier of international development projects.

Possibility of war between America and China

- China prefers to win by improving its position incrementally, patiently. It doesn’t want to risk everything on a single battle. Sun Tzu says that the highest victory is to defeat the enemy without ever fighting.

- Taylor Fravel, a political scientist, found that China used force in only 3 out of 23 of territorial disputes since 1949. Fravel also found that China tends to use its military against opponents that are equal to or stronger than it – possibly as a surprise (see below).

- Allison therefore thinks that China will be patient as they accrue advantages in the Asian region. So long as things are going in China’s direction, it’s unlikely to use military force. China will be cautious about using lethal force against the US because it will take at least another decade for China’s military to match the US’s, even in areas closest to China. But Allison cautions that if the trend of developments in the South China Sea seem to go against China, it might move against the larger US power.

- US doesn’t want to go to war, either. The US has failed to win 4 of the 5 major wars it entered since WWII (Korea, Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan). The American public increasingly doesn’t want to lose lives in combat. China knows this.

- Thomas Schelling has compared nuclear competition to a game of chicken. The country that is more reckless or committed in pursuing its goals (or can persuade the other that it is more reckless or committed), will force the other to take the more responsible act of yielding. But a player who consistently yields can be forced off the road entirely.

- Possible “triggers” for a war include:

- an accidental collision in the South China Sea

- Taiwan moves towards independence

- war provoked by a third party (e.g. Japan)

- North Korea’s collapse

- economic conflict escalating into war

Four cases where China initiated limited war

- Korean War (1950s).

- In 1950, North Korea suddenly invaded South Korea.

- South Korea was close to surrender within a month, until a UN-authorised force (mostly American troops) intervened and drove North Koreans back past the 38th parallel towards the China/North Korea border.

- China gave repeated warnings to back off.

- But Douglas MacArthur, the commander of the troops, didn’t think China would intervene to help the North. The Chinese civil war had just ended and the country was still devastated from it. And America was a nuclear power that had recently forced Japan to surrender.

- China did attack, with around 300,000 men. The US suffered heavy losses as they were caught off guard. The Chinese arm beat the UN forces back to the 38th parallel.

- Allison says that MacArthur asked President Truman for authorisation to use nuclear weapons against China. Truman fired him instead.

- Sino-Soviet border conflict (1969).

- In 1969, China and the USSR clashed in a series of minor border disputes.

- Both sides built up their forces along the border. China had over 650,000 troops while the USSR had 290,000 troops and 1,200 aircraft. But the Soviet forces were better armed and trained.

- The USSR also had over 10,000 nuclear weapons. Many Soviet military leaders wanted to do a pre-emptive nuclear first strike against China and the USSR seriously considered this. They decided not to after they approached the US to find out how it would react, and the US said it would get involved if they did.

- Mao’s China then decided to poke the bear and attack Soviet border troops in the Battle of Zhenboa Island. 91 Soviets and 30 Chinese were killed. The idea was to deter future Soviet aggression and demonstrate that China would fight.

- Taiwan Strait Crisis (1996).

- In 1996, Taiwan had an election. The incumbent Taiwanese president was wanting to move toward independence.

- China tried to intimidate Taiwanese voters by launching missiles and threatening commercial shipping, which the island depended on.

- In response, the US sent two aircraft carriers to Taiwan’s aid. China had to back down.

- China Seas.

- In the mid-1900s, other countries claimed islands in the South China Sea and started construction projects there. In more recent times, China has asserted claims over most of the area and undertaken major construction projects on islands there (e.g. ports, airstrips, lighthouses, radar facilities).

- The reason China wants the South China Sea is to expand its radar and surveillance capabilities. This will help its ships and military aircraft go further and make it harder for US ships to conduct surveillance. There are constantly US naval ships and daily intelligence flights in the China Seas. China wants the US to back off and has made some attempts to do so.

- The US Navy has instructed its ships to avoid confrontation and deescalate whenever China harasses them in the China Seas, but it’s not always successful.

- In 2001, a US surveillance aircraft near Hainan Island in China hit a Chinese fighter jet, which had been harassing it. The Chinese pilot was killed. The US pilots had to make a crash landing in China. The US crew were freed after 10 days but the Chinese held the plane for longer to examine it.

Modern War Technologies

- Satellites are important in wars – they help planning operations, communication, and targeting weapons. The US depends on this more than any of its competitors. Anti-satellite weapons are therefore likely to play a big role in any US-China conflict.

- Cyberwarfare is also likely to play a role. Both countries could use cyberweapons to shut down military networks and critical infrastructure like power grids. Unlike their nuclear weapons, neither country can be sure its cyberweapons could withstand a serious attack. This creates a dangerous use-it-or-lose-it dynamic where each side has an incentive to attack first.

Nuclear weapons

- Allison talks quite a bit about nuclear weapons and how they are unprecedented. (He does it in a strange part of the book – in his “Twelve Clues for Peace” chapter following the discussion of the cold war).

- The idea of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) is that neither side can be sure of destroying its opponent’s arsenal with a first strike before the opponent could launch its own nuclear response. China’s nuclear arsenal is robust enough that it creates a MAD situation with the US.

- Once two states have invulnerable nuclear arsenals, “hot” war is no longer an option. They have to live together and learn to compromise and find ways to avoid war.

- While neither side can win a nuclear war, they have to show they are willing to risk such a war else it will be “nudged off the road” in the game of chicken.

Japan and the US (1899 to 1941) (WAR)

- In 1899 the US announced its “Open Door” policy. That policy declared that the US would not permit any foreign power to colonise or monopolise trade with China. China would be equally “open” to trade with all countries.

- To Japan, this seemed grossly unfair because the US had just colonised the Philippines (its first major colony), the previous year. In 1933, Tokyo announced a “Japanese Monroe Doctrine” declaring that Japan was responsible for peace and order in the Far East.

- The US found Japan’s ambitions unacceptable and saw it as a threat to the Open Door policy. It responded with a series of economic sanctions and embargos. In 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in response.

Germany (Prussia) and France (1800s) (WAR)

- Prussia grew a lot in the 1800s as it incorporated other German states. Its population grew from 1/3 of France’s in 1820 to 4/5ths in 1870. Its military also grew to surpass France’s.

- Otto von Bismarck wanted to unify Germany. But the leaders of the various German-speaking regions wanted to retain their power – they did not want to be subordinate to Bismarck.

- Bismarck correctly recognised that a war with France, in which France was seen to be the aggressor, would help achieve his goal of unification. He did this by proposing to put a German prince on the Spanish throne, which would surround France.

- France saw this as an attempt by Prussia to change the balance of power in Europe, and Napoleon demanded that the Prussian king promise never to put a relative on the Spanish throne. Prussia refused. Napoleon declared war in 1870. Prussia won handily.

Britain and Germany (1900s) (WAR)

- In the late-1800s and early 1900s, Germany was growing fast:

- By 1914, Germany’s population was 50% larger than Britain’s.

- Germany’s economy surpassed Britain’s in 1910. Before 1900, Britain had seen Germany more as an economic threat than a strategic one. More and more people were buying German goods over British ones. Some British politicians had wanted to form an alliance with Germany. By the 1910s, this had changed.

- Germany’s science and technology was very strong too. Between 1901, when the Nobel Prize began, to 1914, Germany won 18 prizes, more than twice as many as Britain.

- Germany’s military, particularly its navy, more than doubled in size between 1900 and 1911.

- Many Germans felt short-changed because, in the previous century, a lot of countries (Britain, the US, Japan, Italy, even Belgium) had colonies. Germany felt it had come late to the table when the world was being divvied up, so it didn’t have anything. (Allison suggests that this is exactly how China feels today.) A lot of Germans believed colonies were essential to Germany’s survival.

The naval arms race

- Kaiser Wilhelm II was the German emperor from 1888. He was only 29. Wilhelm’s mother was born in Britain (she was Queen Victoria’s daughter) and he was fluent in English. While he loved his grandmother and identified with the English, Wilhelm also felt insecure and wanted to prove himself. He did not like the idea that Britain was superior to Germany.

- Wilhelm was greatly influenced by the book The Influence of Sea Power upon History by Captain Alfred Mahan, which suggested that naval strength was the key to great power success. He then directed Alfred Tirpitz to build up Germany’s fleet. Publicly, they claimed that this was to protect Germany’s commerce but privately, they agreed the main purpose of the fleet was to counter British dominance.

- Wilhelm’s uncle, King Edward VII, visited Germany for a regatta in 1904. Wilhelm proudly and foolishly showed off Germany’s shipbuilding program (despite Tirpitz and others’ counsel that they should keep it quiet until the German fleet was large enough to challenge Britain’s). After seeing this, King Edward prepared for war with Germany.

- Since 1889, Britain had committed to a “Two-Power Standard”, under which it would maintain a fleet equal in size to the next two largest fleets in the world. At around the same time as Germany’s rise, the US, Japanese and Russian fleets were also growing. Britain had to accept that it could not maintain naval dominance everywhere. It chose to focus on Germany, which was closest. Britain was determined to see that no single country dominated the European continent, else Britain could be vulnerable to an invasion.

- Churchill tried hard to slow or stop the naval arms race. In 1912, Churchill announced that Britain would drop the Two-Power standard. Instead, for every new German battleship, Britain would build two new ones. But if German suspended its building program, Britain would similarly match that suspension.

- The Germans did not initially like this idea but changed its mind by 1913 because of domestic and financial constraints. While Britain “won” the naval arms race, it still felt uneasy about Germany.

World War I

- In around 1905-1907, Britain formed an alliance with France and Russia (the Triple Entente) because of its concerns about Germany.

- At the same time that Britain was worried about Germany, Germany was worried about Russia. In 1913, Russia announced a “grand program” for expanding its army. Russia’s army was projected to outnumber Germany’s 3-to-1 by 1917. Germany wanted to quickly defeat France before moving East to deal with Russia.

- In 1914, a year after Tirpitz conceded the naval arms race, Germany invaded France. The immediate trigger for this was the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, the nephew to the Austro-Hungarian emperor, by a Serbian nationalist. The assassination caused a conflict between Austria-Hungary and Serbia. Russia backed Serbia. Germany backed Austria-Hungary, its sole ally.

- Germany gave a “blank check” to Austria-Hungary, promising that Germany would fully support it in retaliating against Serbia. Austria issued to Serbia a stern ultimatum. Austria had designed its ultimatum to be rejected because they wanted a war. Serbia ended up accepting all of Austria’s demands. Austria declared war anyway.

- Germany’s plans to quickly defeat France required it to invade Luxembourg and Belgium. Invading Belgium was unacceptable to Britain. Britain had sworn to protect Belgium’s neutrality in the 1839 Treaty of London, and Germany’s invasion of Belgium helped galvanise public opinion to go to war. But Allison argues that the main reason Britain went to war was to protect its own national interests, because it did not want Germany to be the dominant power on the continent.

Spain and Portugal (1400-1500s) (NOT WAR)

- Portugal was dominant on the seas for most of the 15th Century.

- In 1469, Spain was unified by the marriage of Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragorn.

- Christopher Columbus had initially approached Portugal for funds to sail west to find a new route to India. Portugal declined him, but Spain agreed, in exchange for 10% of colonial revenue. This mistake allowed Spain to emerge as a serious rival to Portugal.

- The resulting tensions between Portugal and Spain were resolved by appealing to a higher authority – the Pope. The Pope drew a line from north to south dividing lands between Spain and Portugal. This become the basis for the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494.

Germany and Britain and France (1990s) (NOT WAR)

- WWII ended with a divided Germany, with the Soviets in the East and the US in the West.

- In a bid to reduce the likelihood of future wars, European leaders like Jean Monnet and Robert Schuman fostered trade networks between countries in Europe, particularly France and Germany. These networks grew into the European Common Market (now called the European Economic Community) and, later, the European Union.

- After the Berlin Wall fell, Germany reunified and grew in prominence. But it has remained committed to integrating with its neighbours.

- Allison notes that, even though Germany is strong economically and politically, it has remained “a military eunuch”. It was forcibly disarmed and demilitarised in 1945. The US gave a security guarantee to remove any reason for Germany to increase its military.

America and Britain (1900s) (NOT WAR)

- Relations between America and Britain remained tense after America gained independence in 1776.

- Britain basically couldn’t fight all its threats. Although America was the most powerful of its rivals, Germany and Russia were closer and posed bigger threats.

- Plus, it would be hard to fight America from so far away – there were no credible competitors near America that Britain could enlist as an ally. Canada didn’t have much ability to defend itself.

- So Britain was keen to avoid war at all costs and they were quite good at satisfying American demands (even where unreasonable) without compromising their key national interests. Historians have used the term “The Great Rapprochement” to describe the period from 1895 to 1915, when the two countries came closer together. It was so successful that America became an essential ally for Britain in WWI.

- Allison suggests that if Britain had anticipated America’s rise in 1861, they could have intervened in the American Civil War in 1861. This might have produced a weaker, divided America or two separate nations.

Soviet Union and the US (1940s-1980s) (NOT WAR)

- In 1964, Paul Samuelson foresaw that Soviet GNP would overtake America’s by the 1980s.

- After WWII, both the Soviet Union and the US were exhausted. Many in the US thought that they could not coexist with the Soviets, especially after the Soviets tested their first atomic bomb.

- The two sides invented “cold war” as the conduct of war without direct physical attacks against each other. But it did involve proxy wars (e.g. in Korea, Vietnam and Afghanistan).

- US’s cold war strategy was bipartisan and sustained over 4 decades. They recognised that it was a very long-term problem. The purpose of the cold war strategy was to “preserve the US as a free nation with our fundamental institutions and values intact”. It also involved using allies (notably Japan and Europe) and the creation of international institutions to create the global order as the US wanted.

Other Interesting Points

- Stanley Fischer, a leading professor and central banker, thinks that GDP measured at PPP (purchasing power parity) is the best way to compare the size of national economies. It is particularly useful for assessing comparative military potential as PPP measures how many aircraft, missiles, drones, etc a country can buy based on the prices in its own national currency. (China uses GDP measured at market exchange rates (MER) when it wants to make itself look smaller or less threatening.)

- In terms of catchup in military power, responses may be (grossly) asymmetric. For example, a million dollar anti-satellite weapon can destroy a multi-billion dollar satellite.

- Henry Kissinger, the secretary of state who played a key role in opening up to China, was Allison’s adviser at Harvard.

- Winston Churchill entered Parliament at the age of only 26 and was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty when he was just 37.

- The Black Death was part of the reason Portugal became so dominant on the seas. In 1348, the Black Death killed 1/3 of Portugal’s population. There were not enough able-bodied workers to farm their rocky soil so they turned to fishing.

- The reason Brazil speaks Portuguese while most of South America speaks Spanish is because the line drawn by the Pope dividing the world between Portugal and Spain cut through Brazil.

- George Orwell coined the term “cold war”.

My Thoughts

I found Allison’s writing a bit dense and hard to follow. There were many times that he combined multiple complex ideas into a single (long) sentence. I’m pretty sure my reading pace for this book was slower than average. I was also glad I read this on an e-Reader because I often had to look up terms (and events) with the dictionary.

The structure wasn’t particularly logical either. Allison repeated some points in different places and I certainly found it hard to translate into a summary. One of the reasons is that Allison just combines so much into a single book. His twelves clues for peace were not necessarily coherent. Some ‘clues’, such as “Timing is crucial” or “Leaders of nuclear superpowers must nonetheless be prepared to risk a war they cannot win” aren’t really clues for peace.

Some people may find the title of the book a bit “clickbait-y” because Allison is quick to point out that war between America and China is not inevitable (it’s in the preface, before the book even starts!). He explains that he took the term “inevitable” as Thucydides used it. Allison says Thucydides himself accepted it was hyperbole. It is just more likely than not, especially if people don’t recognise that risk and act to avoid it.

The ideas in the book were interesting and Allison’s arguments appeared reasonably compelling. A possible exception is when he talks about economics.

- For example, he suggests that the US has to be willing to risk a confrontation with China to stop its currency manipulations and domestic subsidies. But I think that most economists agree that there’s nothing unfair about currency manipulation, which is a vague political term without a clear definition. Similarly, there’s nothing unfair about domestic subsidies. The US and many other Western countries have plenty of domestic subsidies, most notably wheat.

- He also talks about China’s incredibly high growth rates of around 10% per year compared to the US’s significantly lower growth rates at around 2%. But he didn’t mention that economists generally think that cutting edge growth for countries like the US who are already at the technological frontier, will inevitably be much slower than catching up growth, for developing countries that started from a low capital base. Although I think he might argue that, even if China’s growth slowed when it reached the cutting edge, the size of China is such that, by that point, China would be much larger than America in overall (not per capita) terms. That’s fair, but could have been more transparent in the book.

Foreign policy is not an area that I know much about – nor is history, really – so I do not feel I am well-placed to judge his claims on their merits. I also expect that foreign policy is one of those areas where people’s theories generally can’t be proven “right” or “wrong” anyway as no one will assign a 100% or 0% probability to any event and we don’t get to re-run history multiple times to see what happens if we change one variable. It’s a field with a very high degree of uncertainty. Allison’s overall argument that China’s rise would likely result in war is at least based on evidence of base rates and not just pure speculation. Of course, as Allison points out – maybe this time is different.

Buy Destined for War at: Amazon | Kobo <– These are affiliate links, which means I may earn a small commission if you make a purchase. I’d be grateful if you considered supporting the site in this way! 🙂

Share your thoughts on this book in the comments below! If you enjoyed this summary of Destined for War, you may also like my summaries of: