[Estimated time: 12 mins]

This is my third post for this series. It refers to concepts ideas in my previous two posts, which are recommended but not required for understanding this post:

I started writing this series after hearing so much discussion about AI’s effect on the economy that really seemed to miss the point. “Optimistic” forecasts suggest AI has the potential to deliver explosive economic growth of up to 20 or 30% per year. Others predicted much lower rates, but still consistently assume that more economic growth will be better.

Personally, I don’t care whether economists expect AI will cause GDP growth of 3% or 30%. How much AI will transform the economy will depend heavily on how capable the technology (especially in robotics) gets, and that is a question more for scientists than economists.

But that’s not to say economists don’t have any useful insights about how AI might transform our economy. They absolutely do. We just shouldn’t let an obsession with economic growth figures blind us to more important questions about how we think the economy could change.

In this post, I argue that we should care less about “How much will AI grow the economy?” and more about “How will the economy change, and who will benefit from those changes?” Because, depending on how AI’s productivity gains are distributed, we could see a world with unprecedented levels of prosperity and flourishing, or a world where most people end up worse-off than they are now, or something in between. And GDP figures aren’t going to tell us which world we’re in.

Optimistic AI scenarios with low economic growth

My last post explained how we care about “economic growth” not because of the level of output per se, but because of the gains from trade associated with that output. Economists love gains from trade, which they refer to as “surpluses”. A “consumer surplus” arises when the gain is captured by a consumer; a “producer surplus” arises when it’s captured by a producer. Crucially, consumer surpluses do not show up in GDP figures, but producer surpluses do.

AI could add a lot of value to our lives if it vastly increases consumer surpluses, even though this would not show up in GDP. My most wildly optimistic ideas for what AI has the potential to do include:

- help develop drugs or vaccines that effectively eradicate diseases like malaria or tuberculosis;

- greatly reduce the prevalence and severity traffic accidents, saving millions of lives;

- drastically lower the costs of education, giving everyone free access to a high-quality, personalised tutor;

- improve the technology for lab-grown meat such that it becomes cheaper than factory-farmed meat;

- develop feasible and scalable carbon capture technology that lets us avoid any climate-related catastrophes without cutting back on emissions; and

- prevent or end wars by finding ways for parties that don’t trust each other to nevertheless “trade” and reach lasting settlements.

These are some of the very best things I think AI has the potential to achieve, at least in theory. Such achievements could save millions of lives (billions, if you include animals), drastically reduce suffering, and enable human flourishing on a scale we’ve never seen before. And they all share a common feature: they deliver value to large swathes of the world’s population at a very low cost.

If these potential gains from AI are shared broadly—a big if—consumer surpluses could balloon even as GDP stagnates or drops. We’ve already seen something similar happen with computing and the Internet. For a long time, computers barely showed up in the GDP statistics even while they transformed our lives, causing economists to puzzle over this “productivity paradox”. We might well see this again with AI. If the costs of AI mostly consist of the fixed costs incurred in setting up and training it, and the market for AI services is highly competitive, we could see AI deliver massive consumer surpluses while barely affecting GDP. Alternatively, if AI helps publicly-funded or charitable researchers make scientific breakthroughs that they share freely, it could potentially benefit enormous numbers of people—again, without significantly boosting GDP.

So my best case scenario for AI is not that it will generate a lot of GDP growth. It’s that AI will deliver large benefits which are shared broadly at little or no cost to recipients.

Less optimistic scenarios with high economic growth

Conversely, there are also various plausible scenarios where GDP soars while general well-being stagnates or even declines. In particular, I’m concerned that productivity gains will be captured largely by those who happen to control certain bottlenecks in our economy, such as land or compute. If this happens, AI may well boost GDP output without improving—and perhaps even hurting—general well-being because gains are not widely shared.

A bigger pie can still make most people worse off

Mainstream economists have a tendency to view distribution as an afterthought. There are no objectively correct answers on how to distribute a pie, and reasonable people can hold very different (and often self-interested) views of what a “fair” distribution might look like. As such, many economists prefer to leave distribution to the messy realm of politics, choosing instead to focus on questions where objective answers might be found. For them, the priority is getting the economy to produce more output—growing the overall pie. A fair distribution would be “nice” but so long as everyone’s slice of the pie is bigger in absolute terms, we’d all be better off. If they aren’t, it’s likely because of something like envy, and policymakers can’t really fix that.

The problem with this “bigger pie” argument is that the supply of some goods (notably status and land, but perhaps also things like rare minerals) is inherently fixed. Competition for such goods is therefore zero-sum and determined by relative wealth. So to the extent these goods matter for well-being, a person’s relative share of the pie may be more relevant than the absolute size of their slice.

Example: Food and Housing

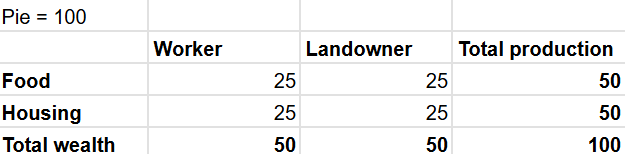

Take an economy where the economic “pie” is 100, made up of 50 units of Housing and 50 units of Food. Assume initially that the units are shared equally between workers and landowners:

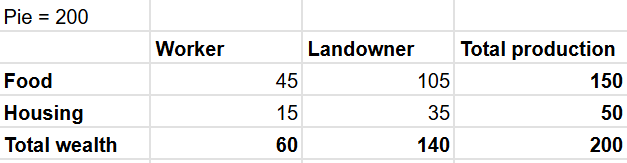

Now, assume that technological advances triple the amount of Food produced to 150 units. The total pie has grown to 200 units.

But let’s say these changes also allow landowners to capture a larger share of the pie—because the supply of land is fixed while demand is inelastic (i.e. everyone needs some land to live on). The distribution might then look something like this:

At first blush, this might look like a Pareto improvement—a change where some people are made better off but nobody is worse off:

- The landowner is clearly better off. Since their share of the pie has increased in both relative and absolute terms, they now have more Food and more Housing.

- Superficially, the worker also appears to be better off. Although their share of the pie has shrunk, the overall pie has grown, so their total wealth has increased from 50 to 60 units.

But what this calculation obscures is that Food and Housing are fundamentally different things, and we need some combination of both for well-being. Workers might value the 10 units of Housing they lost more than the 20 units of Food gained. Such a preference is perfectly reasonable, and is consistent with standard economic theory about diminishing marginal returns and indifference curves. If that’s the case, workers would be worse off even though their “total wealth” has increased.

Importantly, a worker cannot trade 20 units of Food to get back to their original 25:25 mix of Food and Housing, because the relative prices of Food and Housing have changed. Since the productivity of Food increased but the productivity of Housing did not, Housing should now cost 3 times as much as Food.

When you aggregate different things, you’ll inevitably reduce them to a common unit or currency. But once you do so, it’s easy to forget that the things you aggregated were fundamentally different. When well-being depends on any zero-sum good like status or land, the distribution of a pie can be just as important as its size.

The example above has obviously been simplified, but the broad effect it demonstrates seems realistic. Indeed, I think something like this has happened over the past century or so, because productivity increases are always uneven and the supply of land is fixed. This broad effect may help explain why so many feel that life—particularly housing—is less affordable now, even as society has gotten much richer.

Now, what if we saw a more dramatic version of this with AI?

Example: AI vastly increasing the size of the pie

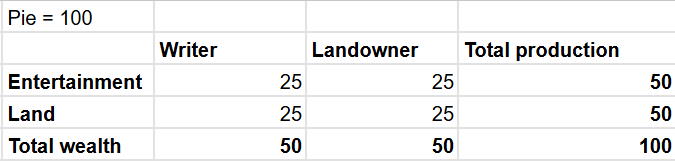

Consider this scenario before AI take-off:

I’ve replaced the worker above with a writer, but you could substitute in a knowledge worker from any part of the economy where you’d expect AI to dramatically increase outputs (software developers, accountants, data analysts, researchers, lawyers, etc). You could also think of “Entertainment” to encompass “Knowledge Work” more broadly if you wish.

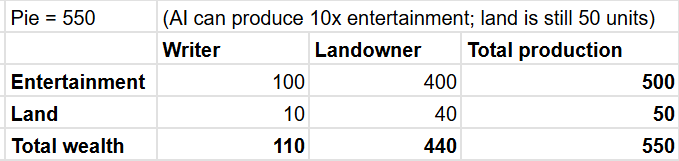

Now, consider a scenario in which AI causes Entertainment output to increase 10-fold without any drop in quality. Note that this does not require AI to fully replace writers—it would be enough if AI enabled human writers (as a group) to produce 10 times as much Entertainment as they did before.

The total pie has grown from 100 to 550. Landowners have received a massive increase in wealth, from 50 to 440—almost 9x what they had previously! Writers’ gains weren’t quite so large, but their total wealth has still more than doubled.

So has AI made everyone much better off?

The problem, as with the earlier example, is that Entertainment and Land are not perfect substitutes for each other. Writers now have a lot more Entertainment, but less Land. If a writer values the Land lost more than the Entertainment units gained, they would be worse off. Writers would only be better off if they preferred the new 100:10 Entertainment/Land mix to their original 25:25 mix.

Of course, this example has been simplified. In reality, we must also account for the owners of all the firms in the AI supply chain—such as those controlling energy, data, chips, and rare minerals. There will no doubt be other bottlenecks in the supply chain, and it is likely that the people controlling those will be able to capture much of the productivity gains.

The above is not even a particularly pessimistic scenario, as it doesn’t assume AI makes human writers obsolete—there is no technological unemployment in my example. If technological unemployment does occur (and I believe it is highly likely there’ll be at least some), the distribution would become much more skewed against writers. Some may end up with almost none of the post-AI pie, save for what they can get through the welfare system or other means. At the extreme, we might see a scenario along the lines of what Luke Drago and Rudolf Laine describe in The Intelligence Curse, where governments are funded by resource rents instead of income taxes and no longer care about furthering the interests of ordinary citizens.

To recap: these examples show how a much bigger pie can still make people—perhaps even the majority of people—worse off if growing the pie alters its distribution. A fair distribution should not be an afterthought as we race towards a bigger pie. If the bulk of AI’s productivity gains end up captured by the relatively few who happen to control the most valuable bottlenecks, we are likely to see global well-being fall even as GDP rises.

Conclusion

As I’ve said before, GDP has never been a measure of well-being, and I believe there’s a good chance we’ll see the relationship between the two further decouple as AI develops. The question we should be focusing on isn’t how much value AI will create. It’s how that value will be generated, and who will capture it.

My optimistic AI scenario isn’t explosive GDP growth of 20-30% annually. It’s AI-driven abundance that’s broadly shared—better healthcare and education; safer transport; solutions to climate change; a reduction in animal suffering and violent conflicts. Such a future might show modest GDP growth, even as it delivers unprecedented improvements in global well-being.

My pessimistic AI scenario is not economic stagnation. It’s AI transforming our society in ways that leave the majority of people worse off—value accruing almost entirely to a rentier class that happened to own the right types of capital at the right time; jobs no longer offering a viable path of upward mobility; and the few remaining returns to labour swallowed up in zero-sum competitions.

The key difference between my optimistic and pessimistic scenarios isn’t the speed of economic growth. It’s the difference between how the gains from AI are distributed. That’s the question we should be focused on: how to ensure AI’s productivity gains translate into shared prosperity. Because there’s no reason to expect this will happen automatically.

What do your optimistic and pessimistic AI scenarios look like? How might we push towards more optimistic outcomes? Let me know your thoughts in the comments below!

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like: